What does the UK’s ‘political realignment’ mean for energy policy?

By Jonny Marshall

Share

Last updated:

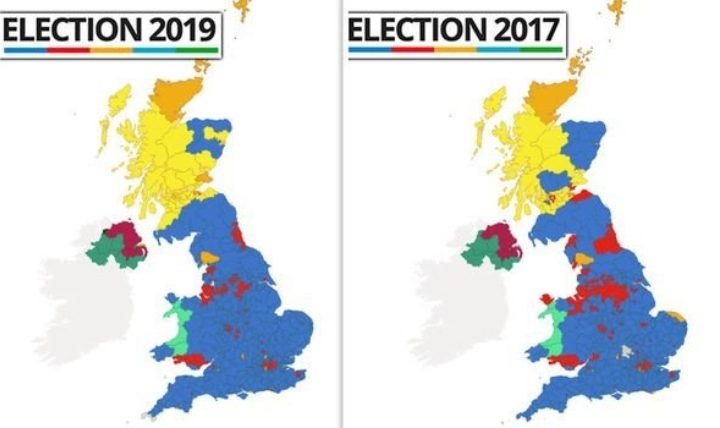

The first slew of analyses of the 2019 election result have focussed on the Conservatives taking control of long-held Labour seats across the Midlands and the North of England. As such, there is no shortage of suggestions that these new voters, who may have ‘held their nose while voting Tory,’ could well feature prominently in policy decisions made by the new administration.

Many of these seats were targeted by Theresa May’s Conservatives, whose offerings on energy policy were to be formed through a controversial ‘Cost of Energy Review’ that would shape thinking for the coming term.

While there were suspected sinister motives behind the review, which was widely ignored across Westminster once certain senior aides were dispatched with, the premise behind its commissioning holds firm. The cost of energy remains a concern for many voters, especially those in newly blue seats. Thankfully, however, the actions needed to help out are clear enough to be instigated from day one.

Northern wall

Despite the months-long election campaign debate around when the UK should be aiming to be carbon neutral, for most of the country the only interaction with the energy sector comes in the form of a bill through the letterbox.

Keeping costs down has long been a mantra of the UK government, and is likely to take on further precedence should the Conservative party pivot to reflect the views of its new voters.

Many of the seats won by the Tories for the first time have higher-than-average levels of fuel poverty. Stoke-on-Trent Central is the highest, with close to 17% of homes affected. Around 15% of homes in the West Bromwich seats are also fuel poor, around 50% more than the national average.

There are more than 100,000 homes in fuel poverty across the 22 English constituencies that are now blue for the first time, Government data shows. One would expect action to tackle this, in the form of both using less energy and making energy cheaper, to be high on the to-do list.

Thankfully, the policy options are not difficult. More low-cost renewables already featured in the election campaign, with a new 40 GW target for offshore wind capacity. But the Johnson majority surely offers space to open the door to new onshore wind, with the dwindling number of Conservative members opposing them outnumbered by those whose have a keener interest in locking in lower energy bills for their constituents.

Wrapping up

2020 will be a pivotal year for other areas of decarbonisation, with housing one of the most pressing. Unsurprisingly, regions with high levels of fuel poverty are correlated with leaky homes. In the same 22 first-time English Tory seats, there are more than 144,000 homes rated at E or below on the EPC register (which only tracks properties registered since 2008).

Policies to tackle energy waste from homes is one of the CCC’s top priorities, and was an early feature of the election campaign. These leaky homes are already set to be offered upgrades under the 2017 Clean Growth Strategy, however progress has been curbed by a lack of policy action.

For a government expected to be less afraid of infrastructure spending and keen to ‘level up’ parts of the nation that have made their voices heard at the ballot box, large-scale action to make homes warmer and nicer places to live would be an obvious place to start.

Bans

It is now no secret that the UK is not making progress on cutting carbon from transport. It is also no secret that calls to bring forward the 2040 ban on non-electric car sales have so far fallen on deaf ears in Downing Street.

However, this is unlikely to be a cause for concern. It is hard to imagine an infrastructure enhancement that appeals to the Prime Minister’s desire to upgrade Britain more than a beefed up electric car charging network. And by first building the system and then pulling tax levers in the upcoming budget, the idea that a ban is the only way to shift demand to electric transport could be debunked.

There is also positivity around action to tackle industrial emissions. With seats such as Redcar turning blue, the promise of investment to safeguard industrial jobs could find itself on the agenda also.

Criticism

Of course, the Johnson premiership will not be without its critics. Climate-wise, the Government is taking flak for setting ambitious long-term goals but not implementing policies to get there.

This angle is entirely justifiable, and is unlikely to go away unless and until the Government comes up with a plan to get on track to net zero, so showing global leadership in the year that the UN climate conference comes to town.

Lucky, then, that a lot of the policies that will appeal to Johnson’s new voters could be the start of this ramping up of ambition.

Share