COP26: Postpone, virtual, or as you were?

Decision on Glasgow climate summit involves more factors than you might imagine

By Richard Black

@_richardblackShare

Last updated:

In today's straitened times, there could surely be no more logical piece of news about COP26, the UN climate summit taking place in Glasgow in November, than that the government was thinking of postponing it.

All around us society is shuttering up, hunkering down, limiting circulation: of course Boris Johnson and his fellow ministers would be wondering whether they can pull off such a big logistical feat on which so much depends.

So far, so straightforward. Except there are many more ramifications to this than meet the casual eye.

Boris's bailiwick?

To start with, a decision on postponing COP26 isn't Mr Johnson's to make. The United Nations climate convention belongs, as the name suggests, to the United Nations – in other words, to all governments that adhere to the climate convention. Which is virtually all of them. The UK merely offers to host and preside over proceedings.

Last year, with just a month left to go before the 2019 UN climate summit, the Chilean government decided that unrest in the streets meant Santiago could not after all play host.

But the Chilean government did not - could not - postpone or cancel the summit. The UN climate convention said it was looking at options - the Spanish government stepped in - and the summit happened.

The same process would kick in with the Glasgow summit. If the UK government decided it could not host, any other government would have the option to mount a rescue bid. Perhaps a government that has handled Covid-19 successfully - options to mention here are Singapore, Japan and South Korea - would stick its hand up.

That might seem far-fetched from where we are today. But no-one thought last year's summit would go ahead after the Chileans pulled out - and it did.

Another point is that there is a whole slew of diplomatic conferences and summits between now and November. Logically you would expect decisions to be taken more or less in chronological order. So far there's been no word of postponing the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM), which according to its website is still set fair for the Rwandan capital Kigali in June.

No word from United Nations headquarters about the UN General Assembly in September, either.

So why are we speculating now about a summit that's further away than both?

Natural conjunction

For environment group WWF, 2020 is a 'super-year'– so called because as well as a UN climate convention summit that's more important than usual, 2020 also sees a summit of its sister treaty, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which is also more important than usual.

The climate summit is special because certain things fall due under the Paris Agreement; the nature summit is special because the existing international targets for restoring nature, agreed in 2010, fall due this year.

It's the first time that both conventions have had 'super-summits' in the same year, with China due to host the CBD in October and the UK the climate COP in November.

See where I'm going with this?

That's right. If having the two summits arm-in-arm this year was a good idea, it's a good idea now to keep them arm-in-arm, and if they are postponed, to do it in tandem.

It won't surprise you to learn then that such conversations are already happening behind the scenes.

Paris promises

Another point concerns what exactly falls due in 2020 under the Paris Agreement.

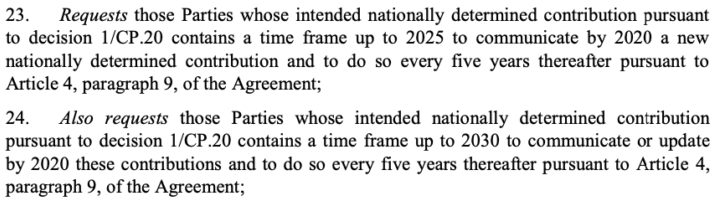

There are a number of things, but two of the most cogent are that governments are due to put forward enhanced commitments to cut carbon by 2030 - so-called Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) - and to submit longer-term decarbonisation plans, to 2050, which ought logically to focus on reaching net zero emissions.

The wording is very explicit: these things should happen 'by 2020', not 'by COP26'.

The same is true of the commitment made originally in 2009 by rich nations to provide, from a mix of public and private sources, $100bn per year to help the poorest nations cut their emissions and protect themselves against climate change impacts. The phrase, again - 'by 2020'.

Now – these commitments aren't legally binding, so governments could collectively decide they want to move the deadlines back. But maybe not all of them will want to, particularly the poorest nations most vulnerable to climate change impacts.

Decision time

Would postponement be a good idea?

There are arguments on both sides. In favour, it's pretty obvious that most governments and businesses and indeed citizens won't have climate change at the top of their priority list in the coming months.

Postponing would also get around the tricky issue of the US Presidential election, which falls on 3rd November – just days before the Glasgow summit.

If a Democrat wins, the logic goes, then holding the summit some months into next year would allow the new President to come along with a package of commitments, breathing new life into the crucial bilateral relationship with China and reinvigorating US diplomacy in support of the Paris Agreement.

On the negative side, every international process like this depends on the 'big mo' – momentum. Any sense of delay, drift, ennui can be a serious detraction.

So, not an easy decision.

However, it's one that governments through the UN climate convention will have to make at some point. Already many smaller preparatory meetings have been cancelled or held online. (The latter isn't a serious proposition for one of the annual summits, by the way – think about trying to conduct a 195-participant conference call spanning every time zone for two weeks, then add in civil society, science, business and all the other interested parties, and you soon see why.)

The convention's next big set-piece is the annual June meeting at UNFCCC HQ in Bonn, conventionally termed the 'Intersessional'. A decision on whether to postpone that will need taking soon – and the one on COP26 will presumably come some time after that, perhaps not until mid-year.

Plans in limbo

A final thought should go to all the organisations up and down the country, but especially in Glasgow, which were looking forward to the UK hosting this hugely important event and whose plans now lie in limbo.

From churches to investment houses, from youth activists to farmers, from emergency services to actors – many and diverse are the people who were planning to mark COP26 in some way, and are now wondering if and when they'll be able to.

It may not be the biggest thing on everyone's mind just now; but when Covid-19 is sorted, climate change will still be there.

And so, perhaps, will the Glasgow COP.

Share