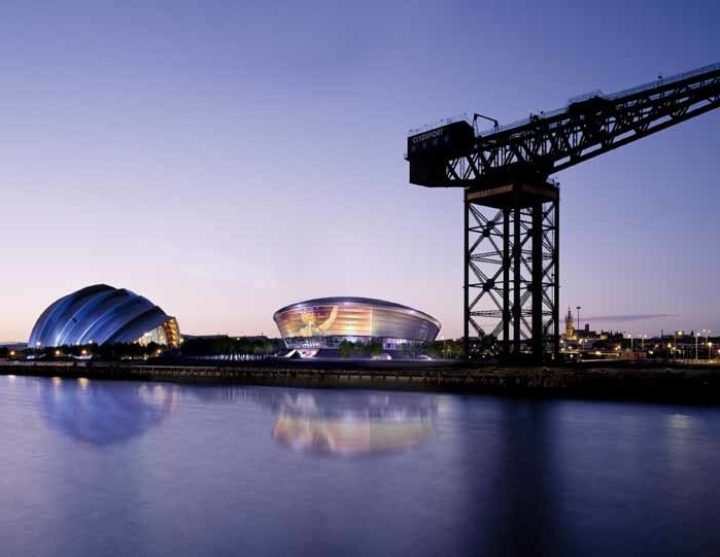

The road to Glasgow, what to expect in 2021

In 2021, in the context of Covid-19 recovery, we are looking a year ahead to the most important climate change summit since the Paris. This blog outlines the long road to COP26.

By Richard Black

@_richardblackShare

Last updated:

One year ago, we were looking a year ahead to the most important climate change summit since the Paris conference of 2015.

One year on, we are once more looking a year ahead to the most important climate change summit since the Paris conference of 2015; such is the havoc that the Covid-19 pandemic has played with the neatly calendared sequence that was supposed to secure implementation of the Paris Agreement.

The pandemic has done more than change the timetable for international climate action. It has changed the politics, the business realities and the general zeitgeist surrounding globally disastrous events: how governments, businesses and citizens think about them, prepare for them and act to ameliorate them. And there are doubtless many further changes to come, as the Covid-19 story veers from vaccine optimism to new variant gloom and back again.

Economically, for many months now commentators have been pointing out that governments can tackle Covid-related carnage and climate change together by ‘building back better’ – investing in jobs-rich low-carbon areas such as renewables, energy efficiency and nature restoration. So far, you would have to say that it is mostly not happening; but there is still much to play for in this area, and ‘building back better’ could do much to shape decarbonisation in the real world as 2021 progresses.

One way in which the UK can play a leading role is as Chair of the G7 group of nations. Logically, this is a forum in which powerful governments could lead collective action to rebuild greener. Moribund though the G7 was in 2020 as Donald Trump morphed from wrecking ball to wreck, Boris Johnson’s government has a spectacular opportunity to use its term at the helm to shape the world’s economic reboot and make it as green as his nature-loving fiancé Carrie Symonds’ favourite wellies.

Covid-19, the disaster and the recovery, will inevitably form the backdrop to how governments tackle the negotiations leading to the delayed COP26 in Glasgow in November. But in terms of the UN process itself, 12th December 2020 – the fifth anniversary of the Paris Agreement – saw a ‘mini-summit’ that was certainly a stock-take, if not quite the turbo-boost that the organisers had hoped.

The virtual Climate Ambition Summit did two things. It brought 75 world leaders together to make statements on their own national commitments to climate ambition; but in doing this, it also highlighted just how much more work is needed the coming year to start to realise the ambition set out in the Paris Agreement.

While the second half of 2020 saw a number of countries, companies and individuals make sometimes startling commitments to cutting emissions – none more so than China’s September pledge to reach net zero emissions by 2060 – there are still gaping ambition gap to be filled. It will be a test of the UK COP26 Presidency to deliver some critical results.

So what should we look out for in 2021?

Finance for vulnerable countries – show us the money

In the Paris Agreement, governments collectively pledged to be delivering at least $100bn per year to the poorest nations ‘by 2020’. This confirmed a pledge first made in 2009 at the UN summit in Copenhagen. But the year ended with nothing like those sums on the table, and the Climate Ambition Summit brought no new pledges of substance.

The UK commitment to doubling its previous funding for vulnerable countries and the low carbon transition in the global south remains. But the government has broken its manifesto pledge by cutting aid from 0.7% to 0.5% of GDP, squeezing all other areas of international aid and causing a huge trust deficit with the least developed countries who are the UK’s natural allies in the climate change negotiations.

In response, COP26 President, Alok Sharma, has made climate finance a core focus of the year to Glasgow and is inviting donor countries to meet with vulnerable nations in March to encourage pledging and delivery of finance commitments that match up to the climate risk in these countries. Public climate finance will also be on the agenda for the G7.

Closing the gap on 1.5°C – make the commitments add up

The number of countries pledging to deliver net-zero emissions by mid-century has rocketed upwards in the last six months, including the big economies of China, Japan, Canada and South Korea. However, the next 10 years will be critical for keeping global warming within the Paris Agreement targets. The UNEP Emissions Gap 2020 report says that to keep below 2oC of global temperature rise will require a tripling of global ambition by 2030, and 1.5oC will require five times current emissions reductions. This places additional pressure on all countries to present more ambitious NDC targets and get on track to delivering them.

For the COP26 Presidency this will require two things: getting countries with net zero targets to raise their short term NDC ambition; and to kick off a discussion on global action needed to close the 1.5°C emissions gap.

President-elect Joe Biden has given some hope here, as the US will re-enter the Paris Agreement and will convene a major economies Climate Summit in his first 100 days.

Real world actions – getting started right now

The COP26 presidency has set five priority areas for ramping up real-world actions to deliver the Paris Agreement. These are:

- Adaptation and resilience: ‘Helping people, economies and the environment adapt and prepare for the impacts of climate change.’

- Nature: ‘Safeguarding ecosystems, protecting natural habitats and keeping carbon out of the atmosphere.’

- Energy transition: ‘Seizing the massive opportunities of cheaper renewables and storage.’

- Accelerating the move to zero-carbon road transport: ‘By 2040, over half of new car sales worldwide are projected to be electric.’

- Finance: ‘We need to unleash the finance which will make all of this possible and power the shift to a zero-carbon economy.’

However, it is not clear what the UK or other entities steering the COP26 agenda envisage as outcomes in these five areas. Previous COPs have launched new UN climate convention work programmes, new intergovernmental processes, public-sector finance initiatives, private-sector alliances… and all of those options would seem to be in play for most of these five areas. The poorest nations will of course be placing great emphasis on adaptation – securing their present and their future against climate change impacts – and this is historically not an area replete with private-sector initiatives.

Across the UK we are likely to see an increasing profile of climate solutions over the coming year as the COP26 campaign expands its #TogetherForOurPlanet initiative, looking to get the British public to take their own actions.

Year-long diplomacy – a marathon, not a sprint

Even with Covid-19 vaccines, it is possible that COP26 will be a much smaller affair than usual. It could be partly held online. But this would be fraught with problems. The smallest nations, especially those in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, would struggle with time-zones – and online UN climate convention meetings this year have thrown up problems with poor connectivity and the slow pace of negotiations. History shows also that summits have to be inclusive, with stakeholders including academics, civil society and media in place. Yet postponing COP26 again – which would have to be considered if participants’ safety cannot be guaranteed – would be a serious blow.

We should garner more information about the realities of international processes in Covid-19 times over the coming months, which feature the Convention on Biodiversity (CBD) negotiations in China scheduled for May; the G7 Summit in the UK and the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in Rwanda in June; the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s next update on climate science in July; and the COP26 co-host Italy’s youth summit in August. All will have action on climate change as a central agenda – if they happen.

And that’s just the bits relating to governments and the UN negotiations. Outside, we can look forward to a busy year for investors, financial regulators and businesses as the changing economics of energy and the risk of stranded assets loom ever larger; to the expanding interest in climate change in areas such as sport and the arts; and potentially to a renewed growth of youth activism, as in-person protests become possible again.

A full year, but a vital one.

Share