Britain's 2019 power cut - one year on

A number of recommendations were made following the events of August 9, are any of them being met?

By Jonny Marshall

Share

Last updated:

This weekend will see the anniversary of the UK’s first major power cut for over a decade. The systemic failings seen on August 9 2019 led to trains stuck on lines, nearly a million people without power and, of course, quick finger-pointing in a bid to make political points.

Rounds of post-match analysis since have shown that a multitude of factors – a lightning strike, tripped turbines, and oversensitive protection gear on generators – were the causes of the lights going out. Though some did, pointing the finger at wind farms alone was, and still is, only possible by discrediting more of the evidence.

The most important piece of analysis and recommendations for action came from the Energy Emergencies Executive Committee (E3C). Since releasing its final report in January, though, E3C has been virtually silent on the issue, even failing to publish the first quarterly update to provide stakeholders with information on how its own recommendations, and those made by regulator Ofgem, are progressing.

This blog will run through the main points raised and those in which progress was expected to be monitored. There are also two summaries (Link 1, Link 2) from last August on ECIU’s website, as well as an Imperial College run-through of the events of the day.

Over-sensitive

Aside from trips at RWE’s Little Barford power station and Orsted’s Hornsea wind farm – both of which have now apparently been updated or recalibrated to make them more resistant to tripping – the main focus of investigations rested on the nearly 500 MW of distributed generation capacity that disconnected, and what could be done to prevent this occurring in the future.

E3C found that the protection settings on thousands of generators was oversensitive, recommending that it ‘should be reviewed immediately’. Many older generators were set to switch off if they sensed the grid’s frequency changing faster than 0.125 Hertz per second (Hz/s), a level of sensitivity that is unnecessarily tight, and one that imposes a not-insignificant cost when balancing the grid.

During the August 9 power cut, system frequency dropped at 0.16 Hz/s, causing many of the most sensitive units to disconnect (and making the situation considerably worse).

Generators connected to the grid since February 2018 are set at a more manageable sensitivity threshold. For those online before this, the Accelerated Loss of Mains Charge Programme (ALoMCP) was designed to fix the problem of oversensitive circuitry, boosting the minimum sensitivity threshold from 0.125 Hz/s to a more-manageable 1 Hz/s. ALoMCP is expected to see the 1 Hz/s target become the norm across the network by 2022.

Initial forecasts were that up to 15 GW of capacity would need upgrading, a figure revised to 20-24 GW as the scheme kicked off last year.

To date, ALoMCP has had three ‘windows’ through which companies apply to make the changes needed, with around 7.9 GW – or more than 4100 individual generators – having undertaken the process.

Good progress: as the number, and capacity, of old and oversensitive units fall, the more resistant the grid will be to disruption. But there is still more to do, especially as the first rounds were generally made up of larger units, which are inherently easier to change than the tens of thousands of much smaller sites, all the way down to rooftop solar PV.

In an attempt to accelerate change, a ‘fast track’ scheme now offers a £5000 payment to owners of the most sensitive kit if changes can be made within 4 weeks. This scheme targets the most sensitive plant, aiming to upgrade any that have a threshold below 0.2 Hz/s.

This will give more breathing room when managing the power system through current tricky times. The application window for this scheme closed in early August, with results expected soon.

Resilient

Another area of focus was inertia and resilience. The ability of a system to ‘ride through’ shocks has lessened as the makeup of our power grid has transformed from power stations with large rotating generators to one based on more renewables and smaller units spread around the country.

As many said at the time, it is always possible to make a system more secure, but doing so incurs a cost – what is needed is a trade-off between the two.

While there has been no update from E3C whether current levels of security and backup (mainly set to cover the largest generator on the system going offline) are sufficient, programmes to boost resilience have been pressing on regardless.

In January, National Grid ESO announced its ‘new approach to stability services’ scheme that will bolster system security, as well as working towards its goal of operating a fossil-free system by 2025.

By setting out how inertia can be provided as a dedicated service, rather than assuming it to be a free by-product of thermal generation, ESO’s plans will see existing plants ‘used in different ways’, such as using power from the grid to create inertia.

With interest in the scheme high, the grid operator has already penned deals for 12.5 GVA seconds of inertia, or in simpler terms, an amount equivalent to that from five coal power stations.

This is not only an important step in breaking away from the old orthodoxy of power system management, but also the explicit creation of another ‘flexibility market’ needed to accelerate the energy transition.

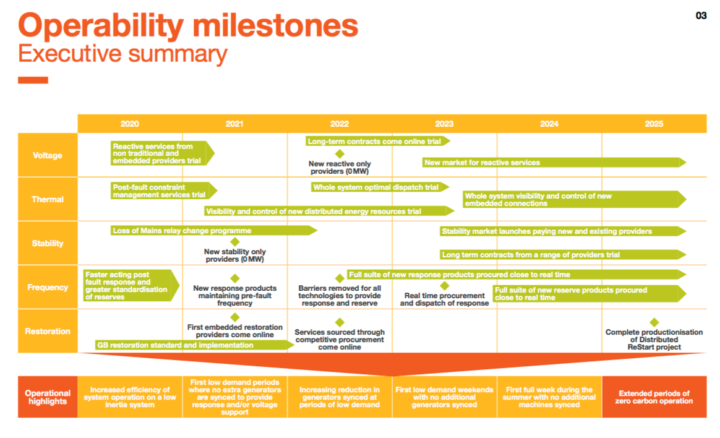

Elsewhere, new plans for frequency response (thereby preventing deviations away from the 50 Hz standard needed to keep the grid ticking over) form part of an ESO roadmap for response and reserve.

New auctions for frequency response services kicked off last November, picking up heavy interest from some of the UK’s most dynamic and innovative energy companies. Experts have been making the case for more flexibility markets for years, and it is schemes like this that are essential in unlocking the vast benefits of a more responsive energy system.

This is manifesting in technological progress already, with Statkraft recently announcing a new flywheel project that will keep the system ticking over, but without using fossil fuels.

The third main development involves research into encouraging renewable generators to provide flexibility services. ESO states that there is ‘no technical reason why intermittent generation cannot provide frequency response’ but at the moment there is no commercial incentive to do so.

Unblocking this is another huge step forward in realising the grid of the future.

Running to 2022 and even covering the potential of a full restart of the grid, this new scheme will bolster system resilience, as discussed in the wake of the August 9 power cut, provide new sources of income for renewable generators and bring the fossil-free operation of Britain’s power system closer.

Black marks?

On a technical level, we can see that there is progress being made. However, another major recommendation following the August 9 power cut was that communication channels within the energy sector and to reach the public should be improved. To the thousands of Brits stuck on trains on a hot August evening, this one is probably the most important.

The lack of an E3C report neatly sums up apparent progress here, showing that there is still more to be done.

In fact, given the summer’s collection of ‘blackouts are coming’ headlines, actions to take control of the narrative earlier would probably have been beneficial. Because despite the warnings of record low demand, new mechanisms to balance the grid, and bungs to inflexible generators to turn off, the power system has raced through summer 2020.

While there may have been the odd scary moment in control rooms, what has happened this summer is an undeniable learning experience, and – along with the technical reforms brought in since the power cut – generally represents a positive step to realising the low carbon, high reliability grid that will power the UK towards its net zero ambitions.

Share