2023’s climate disasters: from storms and cyclones to wildfires and extreme heat

2023 has been a year of record highs and lows for temperature and extreme weather.

By Liane Wimhurst

Share

Last updated:

2023 was the hottest year in human history. The planet was an average of 1.4°C warmer than pre-industrial levels, data from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) showed. There were more greenhouse gas emissions than ever, sea levels reached new heights and Antarctic Sea ice hit record lows. A warmer climate brings more extreme weather, not only record-breaking heatwaves on land and at sea, but heavy rain, floods, droughts, wildfires, and intense hurricanes and storms.

The costs

Aside the immediate devastation to human life and livelihoods, the economic impact of extreme weather is increasing. By September, the US had already had $23 billion worth of damage from climate disasters, a record. These included the Maui wildfire, Hurricane Idalia which struck Florida and a storm in Minnesota, all three of which occurred in one month alone: August. There has been a steady upward march in billion-dollar climate disasters in the US over the decades, from three in 1980, to 23 in 2023, according to data collected by NOAA, which is adjusted for inflation. In October, researchers at the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand found that extreme weather event damage cost $16m an hour in extreme weather damage, study estimates between 2000 and 2019.

For the majority of low-income nations struggling to deal with the impacts of extreme weather, COP28 seemed to offer the beginnings of some solutions: after three decades of negotiations, wealthy high-emissions countries pledged a combined total of just over $700m (£556m) to a new loss and damage fund. However, this is equivalent to less than 0.2% of the irreversible economic and non-economic losses developing countries are facing from global heating every year.

In the UK, June 2023 was confirmed as the hottest June in the UK since records began in 1884. The Office for National Statistics found that only 4% of adults thought the UK was "well prepared" for hotter summers. The impact on food prices is set to continue, with £605 being added to the average grocery bill by the gas crisis and extreme weather in 2023, and the knock-on effects of extreme weather on food imports also driving up UK food prices. A recent Grantham Institute report found that the economic impacts of climate change are likely to increase from 1.1% of GDP at present to 3.3% by 2050 and 7.4% by 2100.

What has extreme weather in 2023 looked like across the world?

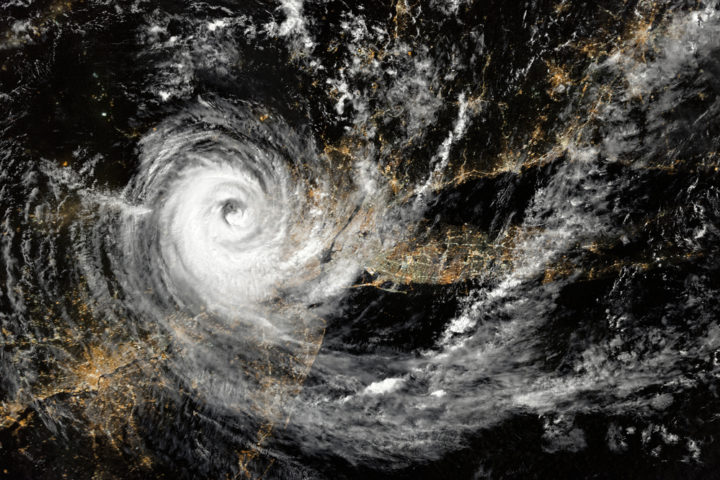

Storms and cyclones

Storm Daniel first battered Greece in early September, destroying farmland in the breadbasket region of Thessaly. Experts said it could take five years for the land to become fertile again. But the storm went on to cause even greater devastation in Libya.

For months this summer, Europe sweltered under an unprecedented heatwave, warming the Mediterranean Sea. This sea surface heat fuelled Storm Daniel as it developed a medicane - a Mediterranean equivalent of an eye to the storm - similar to a tropical cyclone. It then gathered in pace and intensity, barrelling across the Sahara towards the east coast of Libya.

Torrential rain – hitting record highs of 41cm at one weather station – were unleashed on north-eastern Libya. Two inland dams burst, sending a wall of water towards the coastal town of Derna. Streets turned to rivers. Whole neighbourhoods were swept out to sea. More than 15,000 Libyans ended up dead or missing.

Once an oil rich nation, Libya hadn’t fully recovered from crushing battles during the revolt against Muammar Gaddafi in 2011. Like many developing countries on the frontlines of climate change, it was ill prepared for a ferocious storm, and the damage was heightened by poor forecasting systems and weak infrastructure, leading to the unthinkably high death toll.

Cyclone Freddy

The triggers for Cyclone Freddy were similar to those for Storm Daniel. Climate change warmed the sea, creating heat energy from the surface of the water that fuelled the tropical cyclone. It lashed the coast of southern Africa, then circled around and ripped through again, leaving over 1,000 people dead. Another half a million were displaced as it washed away homes, roads and infrastructure.

The month-long cyclone broke several meteorological records. It was the most intense tropical cyclone ever recorded, with the most Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE), a measure based on a storm’s wind strength over its lifetime. The ACE was the equivalent of a full North Atlantic hurricane season, the WMO reported. It was also the longest lasting tropical cyclone on record, running for 34 days, crossing the entire South Indian Ocean and travelling 10,000km.

Freddy also broke records for the most bouts of rapid intensification, defined as increased wind speed of 35 miles per hour, in a 24-hour period. The storm weakened and then built again, sending demolishing winds, storm surges and extreme rainfall across southern Africa. The worst hit areas were in Zimbabwe, Zambia, Malawi, Madagascar and Mozambique. Southern Mozambique was inundated with a year’s rainfall in a month. In Malawi, hundreds died in landslides or as their homes crumbled into floodwaters.

Marine heatwaves

Both Storm Daniel and Cyclone Freddy were driven by marine heatwaves. The oceans have absorbed 90 percent of global warming so far and they cover 70 percent of the Earth’s surface. In 2023, the sea was the hottest it has ever been by a wide margin. In July, a buoy off Florida recorded a temperature of just over 38°C, as if the sea had a fever. Ocean temperatures aren’t tracked in the same way as land ones are, but the highest on record before this was in Kuwait Bay in 2020, at 37.6°C.

In June, there were ‘unheard of’ sea temperatures off the coasts of the UK and Ireland. Marine heatwaves were also reported in the Mediterranean, and off Australia and New Zealand. In fact, a NOAA analysis showed almost half (48%) of the world’s oceans were in the midst of a marine heatwave in August.

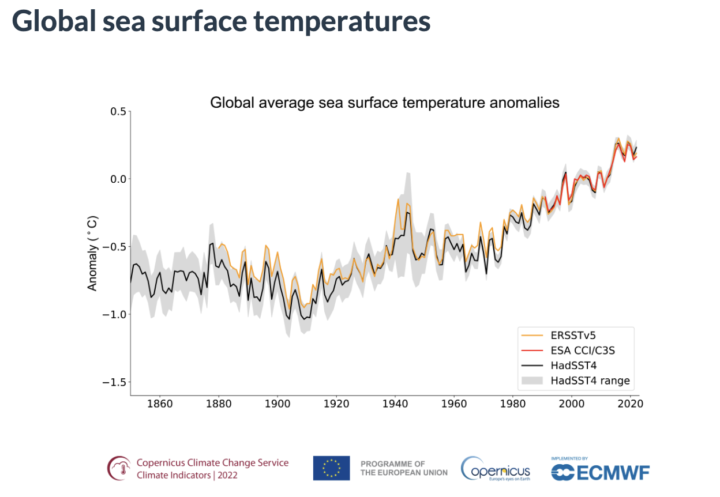

Sea surface temperatures have been rising since at least the early 20th century, along with land temperatures, as ever more greenhouse gases were pumped into the atmosphere. The sea can absorb greater levels of heat energy than land with only a slight change in temperature. But after several decades of accumulated heat, the dial has shifted, and the seas are warming more dramatically, along with greater ocean acidification.

Warmer oceans raise sea levels, bleach coral, melt major ice sheets and cause changes to marine life, ocean health and biochemistry. Warmer seas also provide destructive energy for storms, cyclones and hurricanes. As long as emissions are not precipitously cut, marine heatwaves will continue to destroy ecosystems, causing vast losses of habitats, fish and carbon stores.

Extreme temperatures

The first week of July was Earth’s hottest on record. The northern hemisphere sweltered under extreme heatwaves through the summer. The mercury climbed above 50°C in Death Valley, in the US, which also recorded the highest ever midnight temperature of 48.9°C. China was in the grips of a historic heatwave, with hundreds of weather stations recording record highs in June. Sanbao smashed China’s all-time record with a measuring of 52.2°C, two degrees higher than previous records. Sicily climbed to 46.3°C, and temperatures topped 40°C in parts of Spain, Greece, Italy, Bosnia and France. Meanwhile, Arizona had the longest ever period of not falling below highs of 43.3°C.

Extreme heat is deadly. In Texas, a man died from heat stroke in his apartment after his air conditioning unit failed. By July, Mexico had counted 167 deaths from extreme heat, dozens more than a year earlier. India scorched in heat that killed 170 people. And, in the deadliest year for hikers in America’s southwest parks in at least a decade, several collapsed and perished. 61,000 people died in Europe’s heatwaves of 2022. 2023 was even hotter, but the fatalities have not yet been counted.

As well as extreme heat, disruption of weather patterns also caused unusually cold conditions. In January, Afghanistan – already in the midst of an unprecedented humanitarian crisis - saw temperatures of -28C, resulting in the deaths of 78 people and 77,000 livestock.

Wildfires

This summer in Canada, a record 45.7 million acres of land was ablaze, an area twice the size of Portugal. The wildfires shattered the previous annual record three times over. There were fires everywhere, ripping through Canada’s boreal forests. More than 6,500 erupted in the spring, barrelling across places like Nova Scotia, British Columbia and Quebec. Hundreds of thousands of people were forced to evacuate their homes. The sky turned orange in New York and the smoke spread so far that it was hazardous to breathe the air everywhere from Indiana and Minnesota to the southern states of America.

Wildfires ravaged Croatia, Portugal, Italy, Greece, Spain and Algeria. Greece was struck by the worst wildfires in 20 years, with loss of life, and holidaymakers and locals fleeing as ash fell from the sky. In Rhodes alone, 20,000 people were evacuated. In Algeria, 34 died in flames, in southern Italy a 98-year-old bedridden man perished as a blaze ripped through his home.

On the other side of the world, in Hawaii, a wildfire on the island of Maui killed 99 people. The blaze in the town of Lahaina was the United States’ deadliest fire in more than a century.

What to expect in 2024

El Niño is likely to make 2024 even hotter. El Niño and La Niña are two opposing climate patterns that have global impacts on weather. El Niño developed rapidly in the summer of 2023 and is likely to peak from November 2023 to January 2024, with a 90% chance it’ll persist through the northern hemisphere winter, according to the WMO. El Niño is associated with warmer ocean surface temperatures in the Pacific and normally lasts around 9-12 months, appearing every two to five years.

El Niño impacts typically emerge a year after the weather system develops, meaning 2024 will likely be even warmer than 2023. Heatwaves, droughts, floods and wildfires will be worse in some regions, the WMO warned. This is down to the potent mix of El Niño and climate change. El Niño is a naturally occurring weather system, but its effects are intensified by climate change.