Elections at a time of worsening impacts from climate change

2024 sees elections covering half the world's population and comes after the hottest year on record; yet climate change features little in the pitches of politicians seeking our votes.

By Gareth Redmond-King

@gredmond76Share

Last updated:

The aliens are coming

Imagine there is an alien species from another planet hurtling towards us through space, intent on colonising Earth and eradicating humans. They’re blocking our communications and disrupting our technological and scientific advancement, so things are getting worse for us here, as their arrival looms. (You may, by now, have spotted Cixin Liu’s Three Body Problem in this scenario).

But now imagine we have the means of thwarting this inter-galactic colonisation, and that the brilliant technology to achieve it has myriad knock-on benefits for humans, is cheaper than the mounting problems inflicted on us, and will ensure we are protected against further alien invasions from outer space, long into Earth’s future.

In this scenario – the initial threat, the worsening harm, the existence of a solution, and the huge benefits, security and savings to be had from it – you’d expect to hear about it from your political leaders, right? Even more so, when elections come along, you’d expect candidates and parties to be vying with each other as to who is going to go biggest and fastest to solve this problem and make a happier, safer, richer planet for all human-kind.

You certainly wouldn’t expect leaders in some of the biggest economies on the planet to be denying the problem, demonising those who seek to solve it, and advocating to invite more aliens to come and devour us before the others get here.

Planet Earth 2024

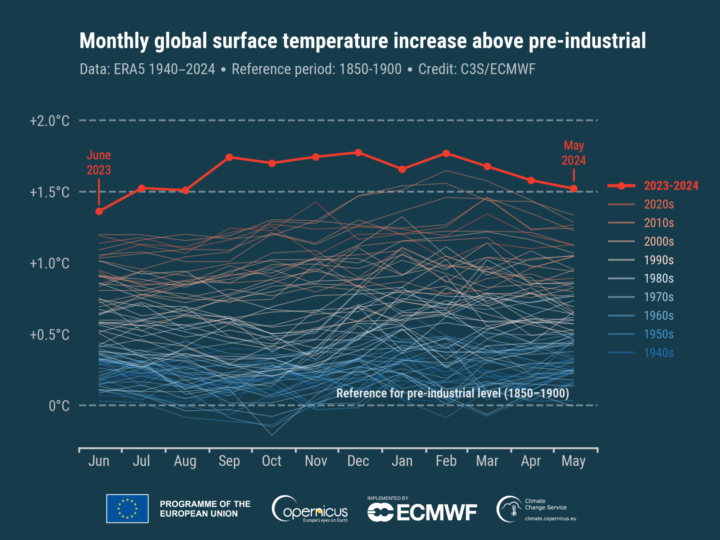

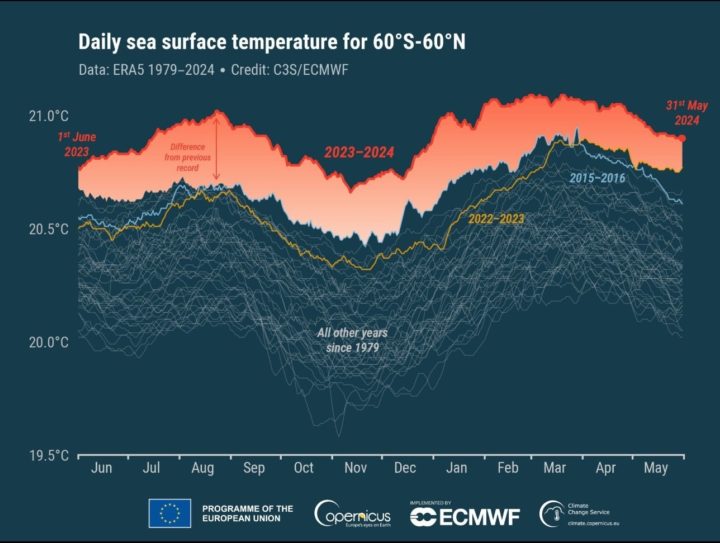

Yet here we are, in 2024 on Planet Earth. Last year was the hottest on record, with average temperatures just shy of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Every one of the last twelve months has set new heat records, and every day over the last year or so has seen higher sea surface temperatures than any corresponding day in previous years.

That extra heat comes from burning fossil fuels and destroying natural systems, leading to the concentration of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere reaching new highs of 427 parts per million (just a decade or so back, 350ppm was reckoned to be a relatively ‘safe’ level beyond which we should not venture).

Ever more dangerous

The disruption to the very life support systems on which we, and every other form of life on the planet rely for our existence has become more evident, more frequent and more dangerous, as scientists have been warning it would for a long time. Not only are these impacts – heat, drought, floods, fires, more intense storms, and rising sea levels – threatening lives, health, security and food, but they risk hitting dangerous tipping points that can speed up and intensify impacts still further.

In recent times, we have been warned of ice sheets in the Arctic and Antarctic becoming more unstable and threatening runaway sea level rise. We have been warned the heat, atmospheric disruption and influx of cold freshwater in oceans could cut off currents that regulate our seasons – on which agriculture and even the liveability of some regions rely. We’ve been warned of species extinction, of decimated rainforests becoming emitters rather than removers of carbon, and of the release of massive quantities of methane from melting Arctic permafrost which could rapidly accelerate heating.

Magic bullets

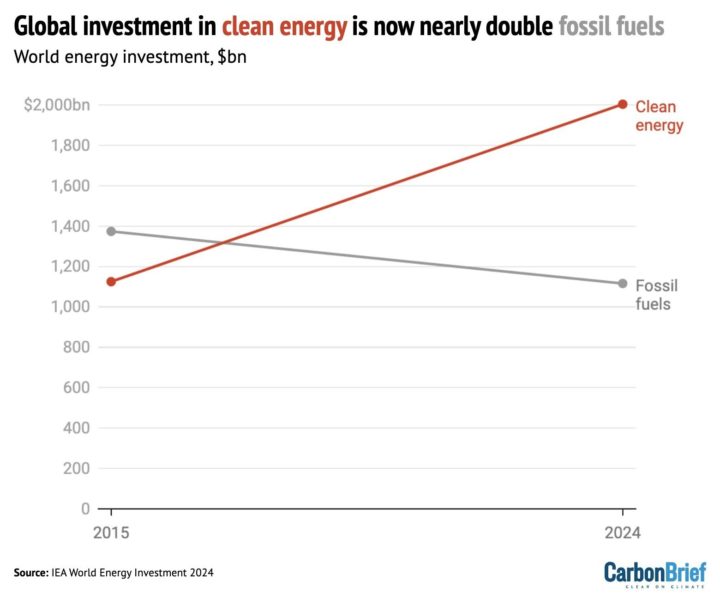

So far so apocalyptic, and yet we have the magic bullet – the brilliant technology – to save ourselves. The main renewable means of generating power, heat and motion – wind and solar – are cheaper than their fossil fuel counterparts. They are being invested in at double the rate of fossil fuels – principally by the biggest emitters on the planet (China, the US and the EU) – but not yet fast enough to halt and reduce the emissions that are fuelling the worsening impacts.

Going further and faster – fast enough to save us – creates jobs, and economic growth. It also saves money as we avoid the impacts that are running at some six times the cost of the solutions. It protects lives, improves health, strengthens food security, cuts the cost of living, and promises a lifetime of clean energy without massive extraction, burning and pollution.

Bumper election year

Yet in this year, 2024, with some 65 elections world-wide, covering half the planet’s population, you would often not even know that we face such dangers, nor that we have the solutions.

Everywhere you look – and pretty much everywhere you poll – people worry about climate change and they want politicians to act to avoid worse into the future. People want to protect their children’s futures. But there is little evidence of the people of Pakistan, Indonesia, India, Korea, South Africa, the US, the European Union, or the United Kingdom (to name a few nations with elections this year) being offered the solutions as the top priorities of the candidates vying for our votes.

Instead, we have would-be leaders who are rowing back on promises in the face of (demonstrably false) claims that the solutions to climate change are too expensive, constrain people’s freedom, or even pose a bigger threat.

Some of those leaders take money for their campaigns from the companies whose profit and power has been built from extracting coal, oil and gas – companies that want to keep generating those record profits they’ve made recently from Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine. Some of them even sat down to dinner with a candidate for one of the most powerful offices in the world who asked them for $1bn in exchange for a bonfire of climate policies, were he to be elected!

At least, in the European Parliament elections, however, the results do not show evidence for the 'green backlash' that many journalists eternally quest to find. Electorates essentially voted on 27 different sets of key issues in 27 member states, and the centre of European politics - the majority that delivered stronger climate targets and laws - looks intact. And whilst the Green/EFA bloc is down from it's all-time 2019 high, it is still a substantial bloc, and Greens led the polls in some places.

The politician reality gap

The gap between the reality of worsening climate impacts and the willingness of candidates across the planet to take up and champion the attractive, cheap, beneficial tools to solve, has quite the power to shock. Or at least it would, if we hadn’t so normalised this discourse and grown dangerously weary of democratic politics in too many parts of the world.

Yet there is evidence in the United States that promised climate action may have swung the outcome towards Biden in 2020 - and could do so again this time, if politicians play up the positives of the Inflation Reduction Act, which Republicans have sought to demonise despite the investment IRA has directed into their own states.

And here in the UK, net zero industries contribute £74 billion a year in value to the British economy, and support three quarters of a million jobs.

How, in both countries, are these wider economic benefits not core to candidates' campaigns?

Vote wisely

We have one solution to limit temperature rises enough and at a level to stabilise and avoid runaway climate disaster: net zero emissions within the next 25 years.

We have all the clean energy solutions we need to achieve that – or at the very least, to get on track this decade. Next decade, with the right R&D now, we can turn our attention to the technology to store emissions, and extract more from the atmosphere – those we don’t have at scale and cost yet. Although, in the meantime, rather more protection and expansion of nature's own groundbreaking carbon capture technologies (trees, peat, mangroves etc) would also be wise.

We also know we have to adapt to the temperature rises we have already caused – but that there is a point of no return beyond which we cannot adapt. Which, of course, is why the Paris Agreement seeks to limit heating to 1.5°C.

We know how to adapt, but most parts of the world that need to adapt most urgently – those most exposed to climate’s impacts – cannot afford it. They need the help of wealthy countries, like the UK, and the US – nations which not only can afford to help and to adapt at home, but whose security, wellbeing and food supplies rely on it.

So, as voters, wherever we are amongst the 4bn people whose countries are holding elections this year, we need to ask about this gap. If we want to deploy the tech to stop the aliens from landing, we need to give our politicians a prod, and then we need to cast our votes wisely.