Not 'just 1% of global emissions'

As Ministers slow some key net zero policies, once again the argument that the UK is 'only 1% of global emissions' resurfaces, implying we've done our bit. Once again, we look at why that's not true.

By Gareth Redmond-King

@gredmond76Share

Last updated:

Throw another log on the fire. Time for one of my favourite annual traditions – explaining afresh why the UK is not ‘just 1% of global emissions.’ This classic has risen again of late, in relation to the UK government’s slowing of some of its climate policies. With plans to require landlords to raise energy efficiency standards scrapped, and the date for ending sale of petrol and diesel vehicles delayed, ‘just 1%’ has resurfaced in mitigation, alongside the inevitable ‘and anyway, we’re world leading in our emissions cuts – what about China?’.

It is true. We have nearly halved emissions since 1990 – a deeper percentage cut than other G7 nations. Only Germany has cut by more than the UK in absolute terms, although from a higher base. However, in more recent years, their rate of cutting emissions has started to overtake the UK – since 2016, Germany cut by 17%, to Britain’s 14%.

The UK was the first major economy to set a legally binding target to get to net zero by 2050, and we do have one of the most ambitious targets for emissions cuts (at least 68% by 2030). However, proponents of the ‘world leaders’ case seem unfamiliar with Aesop’s Tortoise and the Hare, and what happens when you rest on your laurels.

UK is barely 1% of global emissions…

Firstly, though, the 1% claim is only true when we look at emissions within our borders. Analysis conducted in 2020, drawing on 2016 emissions, showed the UK’s true carbon footprint was nearly twice what we emit at home. That is when you include emissions generated elsewhere in the world to supply stuff we import, or by things we do outside the UK – imported fossil fuels, international flights, and manufactured goods, for instance.

But even at less than 1%, we’re still amongst the top emitting countries – number 21 amongst individual nations, on 2022 emissions. And nearly a third of global emissions come from accumulated countries whose territorial emissions are each 1% or less of the global total; around half from nations that account for less than 3% each.

If every one of those nations were to sit back on their laurels and demand that China, the US and India sort the problem alone, then we will fail. Slowing action everywhere else, and waiting for big emitters to ask, makes the problem worse in the short-term, the job harder and more expensive in the medium- and long-term.

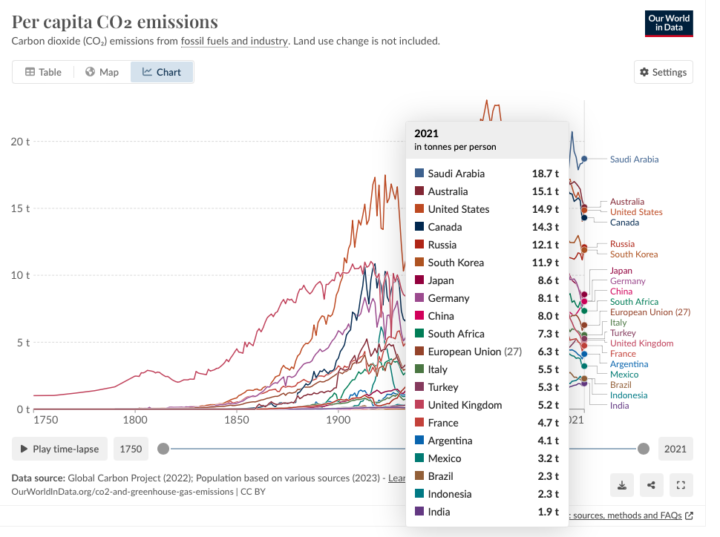

Amongst G20 nations, we ranked 17th for CO2 emissions in 2021. We creep up the list when you count emissions per person. Then we’re 14th among the 20 wealthiest nations, emitting just over five tonnes of CO2 per head. (We’re lower down the overall list, but that compares us with some poorer nations with tiny populations). The average British person’s emissions are around 170 times those of someone in the Democratic Republic of Congo, 14 times the number for Kenya, nine times that in Bangladesh, and just over two and a half times the emissions of each person in India. And whilst China is the single biggest emitter in the world, it is middling amongst G20 nations for per capita emissions, at 8 tonnes per person.

…but a lot more historically

Even if all this wasn’t true, the UK is still one of the top 10 all-time biggest historic emitters. We literally invented burning fossil fuels to make, move and power stuff – the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution. That’s not water under the bridge – that’s emissions literally still in the atmosphere, causing the climate crisis we face today. This is built into the UN process, and the Paris Agreement, putting greater expectation on wealthy developed countries not just to cut emissions earlier, but also to provide financial support and assistance to less wealthy, developing countries.

Leadership

Leadership is also important; and the UK is influential. We are the sixth biggest economy, belong to the G7 and G20 groups of industrial nations, are permanent members of the UN Security Council, and a founding member of NATO. And just two years ago we held the UNFCCC presidency and hosted COP26 in Glasgow.

When influential nations set ambitious emissions targets, and act to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement, others follow. The UK led on deploying renewables over the 2010s, significantly cutting emissions from our power sector. It led the way in 2008 with the Climate Change Act, putting emissions targets into law; and again in upping that target from 80% to net zero emissions by 2050.

It's not just about showing that something should be done, or that it can be done – although those are important. When a wealthy nation does what the UK did in scaling and innovating public investment in renewables since 2010, it has an economic impact. We were the single biggest global market for offshore wind for much of the last decade. That scale of investment and deployment kickstarted the industry, driving innovation and technological development, and bringing costs down sharply. UK leadership helped make the technology better and more affordable for others.

Costs and not

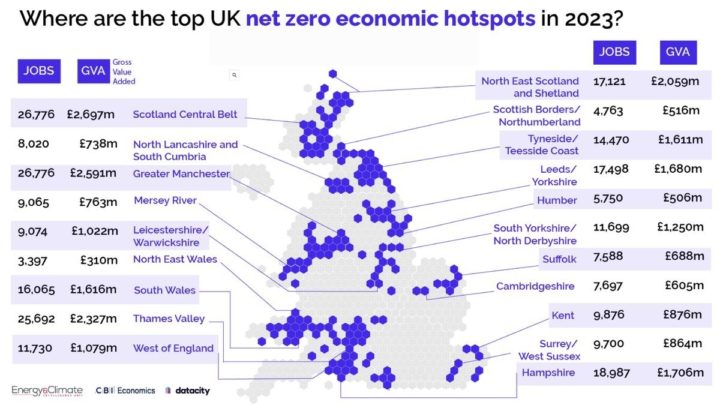

That was not some self-sacrificing act of altruism, taking a hit as first mover. That decade of leadership set us, by 2023, with net zero industries worth £70 billion to the UK economy, and employing 840,000 people – some four times the numbers working in oil and gas.

That investment also got us to the point where nearly 60% of our power generation is low-carbon – 44% of power generated from renewables, which is more than the share generated by gas, as coal-generation dwindles to nothing. That is real energy security – replacing imported fossil fuels with home-grown renewable generation. Offshore wind is now cheaper than gas so any new wind farms, displacing gas power, brings bills down. This has just been reiterated by the National Infrastructure Commission which advised government that the £30 billion a year public investment needed, to leverage much greater private investment, will bring household bills down by £1,000 a year. And the Climate Change Committee warned that the UK’s slowing on certain net zero policies will likely raise energy and motoring costs for households.

The last couple of years has demonstrated the volatility of fossil fuel prices, along with the world’s reliance on Russia and the Middle East. Analysis this year showed that, had we gone faster and further on net zero solutions, household energy bills would have been around £1,700 lower than they were at their height; that cost exacerbated by an average £400 additional on people’s food bills, driven by gas prices and climate impacts. The extent of our continued reliance on gas added some £60 billion to the UK’s energy costs overall, and policy delays announced in September may put another £8 billion of costs into the system, to be borne at least in part by bill-payers.

Done our bit?

Given the benefits, and the costs of not going further, slowing that progress now seems an odd choice; to sit on the side-lines, lauding our own leadership in having ‘done our bit’ and we can now leave it to others, a curious next chapter in the story.

When you stop leading, others pass you by. Globally, clean transition has become a race. China accounts for more than a third of the world’s clean technology exports and their share is growing faster than anyone else. In summer 2022, the US Congress passed legislation committing around half a trillion dollars in investment and incentives for deployment of technology to fuel the clean transition – a shiny beacon to lure clean tech companies to invest in American jobs. The European Union set out to compete, with the added incentive of cutting its reliance on Russian gas. They are in a race to the top to attract and grow investment in the transition to net zero, both attempting to challenge China’s dominance.

Meanwhile, despite a rapidly speeding transition to electric vehicles, dramatic emissions cuts, jobs and investment in all parts of the UK, and that £70 billion a year of added value, the UK government is sending signals to markets and clean tech industries that we might just sit this race out now…

But China!

China is building clean power at a phenomenal rate. As of mid-2023, nearly a third of China’s installed generating capacity and three quarters of all new generating capacity installed this year is renewables. They’re the biggest market for offshore wind and for electric vehicles, and the biggest manufacturer of solar panels.

Sure, they’re building new coal power generation, but that is short-term to keep lights on and industry fuelled in a rapidly developing economy that still needs to bridge the gap the UK bridged long ago, to tip away from fossil fuels. This gigantic economy is making huge investments in renewables because they know it is good economics. But it is also good geopolitics.

Globalised world

We live in a globalised world; climate change respects no borders and costs of climate impacts are rising. We have seen worsening impacts in the UK – the new record of more than 40°C caused 3,500 additional deaths in summer 2022. With half the world’s population exposed in climate hotspots, impacts are worsening everywhere. Even when we don’t feel them here, they hit us. We import half our food from overseas; half of that we could not simply grow here instead. Much of it comes from parts of the world even more vulnerable to climate impacts. That is just one example of the way in which cutting emissions to limit climate change is directly in our own self-interest. But so too is supporting poorer nations to adapt to these worsening impacts.

This is why UK Export Finance – an arm of government – spends nearly £9 billion a year to help British businesses invest overseas. In 2021, some 40% of that was specifically on clean transition. When President of Kenya, William Ruto, says that his and other African countries want to “leapfrog this dirty energy and embrace the benefits of clean power”, he is signalling the scale of the opportunity for investment in new and emerging markets.

What we spend on climate finance (£11.6 billion over five years – though going a little slow on delivery to-date), and overseas development assistance (ODA – £12.8 billion in 2022, albeit a growing proportion is spent in-country, on costs of housing those applying for asylum) is much smaller, but no less an investment. Securing the stability and viability of some of the poorest nations in the world helps stem extremism and prevent people being forced to leave their homes to migrate to other countries. It also helps shore up UK supply chains – the UK Climate Change Committee recently warned that a fifth of economic value of overseas supply chains serving UK consumption was in areas of ‘medium’ to ‘very high’ risk of climate hazards.

And if it’s not the UK investing and supporting developing nations, then who? Well, China already are.

Not ‘just’ anything

We’re not ‘just 1%’; we’re a major economy and one of the top ten historic emitters. The atmosphere and climate system don’t care where emissions come from, and worsening climate impacts anywhere are terrible news everywhere.

We’re wealthy and advanced enough to be able to keep on leading, if we choose. We risk that wealth, and the influence of ‘global Britain’ if we don’t. As the US and EU compete with China to attract investment, and having been at the forefront of not just the first, but also the second and third (electricity and electronics) industrial revolutions, why would the United Kingdom not want to remain at the forefront of this latest revolution?

Share