10 things we learned from the UK general election

What are some of the things we learned from the UK's 2024 general election for climate and energy – in the UK, and beyond?

By Gareth Redmond-King

@gredmond76Share

Last updated:

In common with nearly seventy other countries this year, the UK just had a general election. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak called the election whilst his party, then in government, were some 20 points behind in polling. Results confirmed the polls, and Keir Starmer became Prime Minister on a landslide that gives his Labour government a majority in the House of Commons of 172, and sees the Conservative opposition fall to their lowest seat-tally in history.

What are some of the things we learned from the campaign, and the result of this general election, for climate and energy – in the UK, and beyond?

1. Climate policy row-back doesn’t close polling gaps

Trailing in opinion polls, fearful of growing challenges from the right of his party, UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced last year he was slowing several net zero policies. On top of actual changes (like delaying the ban on sales of petrol and diesel cars), he also stopped some imaginary ones (like meat taxes). Since then, the gap between the Conservatives and the now-governing Labour Party has remained consistently in the high teens/low twenties. Voters tempted by the right in the UK, like those shifting to far right parties in the European Union of late, care about immigration and – in common with most voters everywhere – the cost of living. The election result echoes repudiation of anti-climate measures by the governing party in Australia’s last general election. The UK House of Commons now has nearly 500 out of 650 seats held by MPs from parties offering ambitious climate change policies. That’s as against just short of 120 won by the Conservative Party, and just 5 by Reform, the only party to take an anti-net-zero far right position.

2. Polling pretty much any set of voters shows concern over climate change

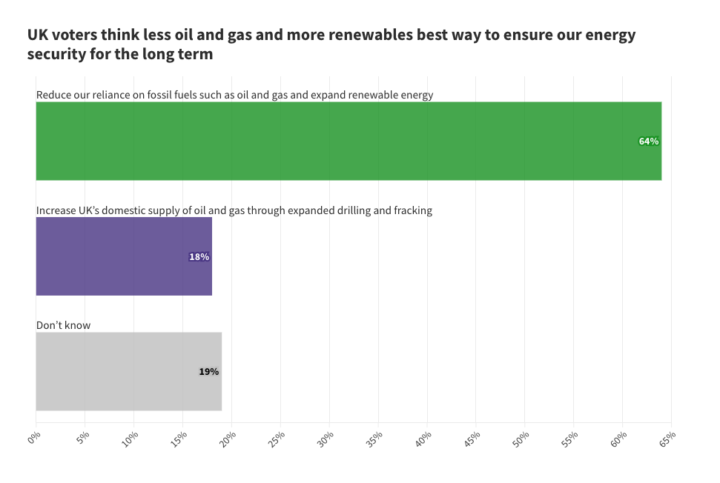

Polls in the UK, US, EU, and pretty much any country, shows that people are worried about climate change and want leaders to tackle it. In the UK, that support was particularly strong amongst voters in a swathe of formerly Conservative seats in the south of England dubbed the blue wall, and could be found amongst voters switching from Tory to Labour. Rural voters are more concerned than the general UK public, as are farmers. Voters generally prefer prioritising renewables over fossil fuels when talking energy security, but MPs in the last Parliament underestimated voters’ support for renewables.

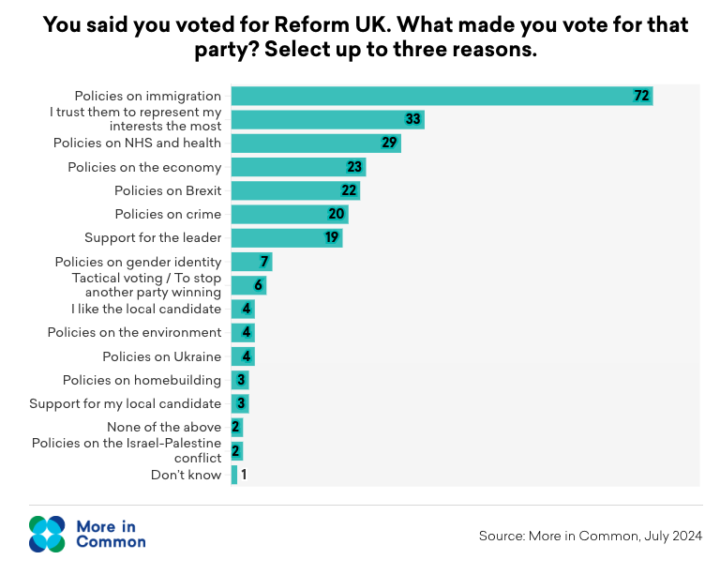

But additionally, polling immediately after the general election – by More in Common, and by ECIU – helped make clear that Tory government’ row-backs on climate policy lost the Conservative Party votes from the centre (to Labour and Liberal Democrats), and that anti-net zero positioning quite clearly did not boost those further right, who were trying to use net zero as a ‘wedge’ issue (with climate change figuring as a top issue for just 4% of Reform voters).

3. Economic growth was a central promise; ‘green’ offered as key to that by Labour

In a cost-of-living election, focus on a struggling economy with recent high inflation was inevitable, and energy costs played their part in the discussion. The Tories focused on North Sea oil and gas for energy security, and had begun to argue that net zero policies simply added costs, when the weight of evidence globally shows that the costs of acting are far outweighed by the growing costs of climate impacts, and evidence here shows delivering net zero policies lead to savings. Polling – and, indeed, the result – showed the public more convinced by Labour’s focus on renewables for energy security, as the party leaned in to green investment for greater prosperity and lower bills.

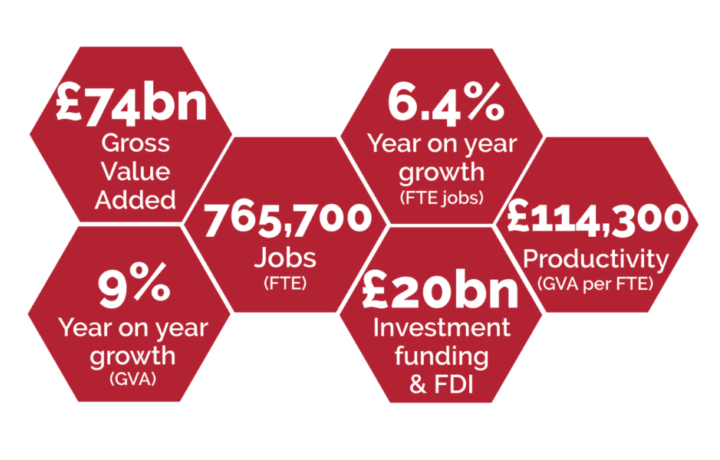

Net zero industries in the UK add £74 billion a year in value to the UK economy, support three quarters of a million jobs, and grew year on year by 9%. In a manifesto otherwise cautious on spending pledges, some of the biggest commitments were £5bn investment in a Green Prosperity Plan, alongside billions to build gigafactories, establish a national wealth fund, and capitalise the flagship GB Energy with more than £8bn over the parliament. At a time of global momentum and competition on clean transition investment, principally between China, the US and the EU, this sends serious signals about the UK’s commitment to lead on climate and desire to attract investment. Experts have already warned of tough decisions ahead to achieve spending likely to be needed for growth; the centrality of clean transition to the new government’s programme suggests this is where it will be seeking to leverage greatest investment in recovery and growth.

4. UK will be the first G7 nation to impose a new oil and gas licences moratorium

Labour come into government with a world-leading commitment to impose a moratorium on new North Sea oil and gas licences. This was not an easy promise to make, given pushback on jobs from unions, and fightback by fossil fuel companies claiming it will jeopardise UK investment. But Labour’s win in the face of that may well reflect lingering public fury at excess profits made by oil and gas majors off the back of Russia’s war against Ukraine, amid soaring domestic energy bills. Their commitment is also one that recognises that the transition needs to be managed in a way that supports people, creating good jobs, using the skills of existing energy workers, and ensuring there is “no community left behind”. Labour’s manifesto also, tellingly, included further commitment to a windfall tax on those companies to fund some of its new green investment – a tax voters seem not to worry about going up.

5. It’s sinking in that North Sea oil and gas are not the solution to energy security

Rather, it appears that voters have chosen an offer of clean, homegrown energy being the solution to energy security. After more than two years of high energy bills driven by volatile fossil fuel prices, caused by war, the central offer of a state-run clean energy company in the form of GB Energy proved popular, alongside that moratorium on new oil and gas licences. Polling published just after the election bears this out.

6. Climate impacts don’t take a break for democracy

It’s a bumper year for democracy worldwide: elections in countries home to half the world’s population. But after last year became the hottest year on record, with each of the twelve months from June 2023 onwards breaking new heat records, and daily highs for sea temperatures for over a year, 2024 is also shaping up to be a heavy year for climate change impacts. In India, extreme heat has killed people; amongst them poll-workers supervising voting in the world’s single biggest exercise of democracy. More than 1,300 worshippers performing Hajj rituals in Saudi Arabia died in temperatures nearing 50°C. And a heat dome has settled over the United States earlier than last year’s, just before hurricane Beryl, the earliest category five Atlantic hurricane on record, hit the Caribbean. And here at home, the wettest winter on record has hit farmers hard. Worsening impacts threaten lives and livelihoods, security and global food supply chains. As cost of living issues continue to loom large as a key issue for voters, they are a reminder of the threat posed both by failing to reach net zero emissions to limit further dangerous impacts, and by wealthy nations failing to step up the climate finance needed by poorer nations to adapt to climate change.

7. The science of climate is settled and not seriously at issue in UK politics

Debate around net zero policies were focused on climate solutions – the relative costs and benefits, risks and opportunities of the switch to EVs, to heat pumps, and to clean electricity. But also about the interaction between climate policies and other top issues for voters – how cleaner power can cut energy and food bills, for example, as well as the jobs and economic benefits from growing net zero industries. Only the far-right Reform Party’s manifesto included relics from climate denial playbooks of old, saying the climate has always changed, and suggesting we adapt rather than cut emissions. But even they edited a later edition to remove that, perhaps finally recognising that we need to both, and British voters don’t buy climate denial these days. Polling during the campaign, and then also afterwards, showed that Reform’s policies on climate and energy were not the principal driver for why some voters turned to them..

8. Far right surges aren’t always what they’re bigged up to be in advance

As we discovered in recent European Parliament elections, a rise in support for the far-right is not uniform, and not a given. Here, despite polling in the mid-teens ahead of the election, at one point over-taking the Tories, the right-wing Reform only secured 5 seats, and a share of the vote slightly lower than some of their polling during the campaign. During the campaign, under greater scrutiny than they had been before the election, media exposed extreme views amongst some Reform activists campaigning in the party leader’s constituency. And the party also stood out for pushing an old-fashioned form of climate denial that is largely anathema in the UK now. At one point, talking about CO2, their funder and president, Richard Tice, was even ridiculed for talking about volcanoes causing climate change…

9. There was considerable anger about environmental damage

Anger over wider environmental harm played a part in this election. Poor enforcement and under-regulation of private water companies have led to huge levels of sewage being pumped into British waterways and coastal areas. So much so, that at the world-famous University Boat Race in London this year, rowers were warned to avoid going into the water. Some areas of the country have even been warned to boil tap-water before drinking it. Fury from all over the country, particularly in more rural and coastal areas often represented by Conservatives, was evident throughout the campaign – helped by some prominent side-campaigns from organisations like Surfers Against Sewage, and former punk singer, Feargal Sharkey.

10. However, there is still a job to do to get better about explaining climate to electorates

The UK has built a fairly strong political consensus over the last couple of decades on tackling climate change; climate denial has largely subsided into conspiracy theory fringes. Partly as a result, the country has made considerable progress on decarbonising – most notably power – and has been a climate leader internationally. Whilst some of this is true of the European Union – particularly in the rush to get off Russian fossil fuels – it is by no means true of all member states, and in some, there has been pushback on some climate policies. Whilst this may have encouraged some on the far right to use net zero as a wedge culture war issue, polling suggests that it was not actually a significant driver of far-right voting – unlike immigration, and cost of living concerns. But here, even with climate action investment as a core part of the winning party’s manifesto, it could hardly be said climate change played a central role in the campaign; far less prominent than at the last election in 2019. This, despite strong support for action on climate change in polling, and given evidence from the US that campaigning on climate change may have swung the election for Democrats in 2020.

Share