Energy efficiency of English homes – what’s causing the increase in standards?

By Jess Ralston

@jessralston2Share

Last updated:

Key points

- Labour Government legacy programmes made a big difference to the number of homes meeting energy efficiency standards, but it’s been downhill since the mid-2010s.

- Existing regulations have also helped make some headway, but they have tailed off, leaving us still heavily dependent on gas – and the most exposed to volatility in gas prices in Western Europe, according to the International Monetary Fund.

- While some people scrabbled around to install insulation during the crisis, this was too late to prevent the Government (and therefore taxpayer) having to shell out billions to cut energy bills for homes that are wasting huge amounts of energy.

- And with energy independence top of the agenda, insulation and reducing gas demand altogether remains one of, if not the, most important step towards achieving it – or face importing more and more gas from abroad as North Sea gas continues its inevitable decline.

During 2022, when the gas crisis caused energy bills to soar, poor insulation and reliance on gas boilers in UK homes resulted in costs of over £3bn to the country as a whole. The International Monetary Fund pointed to our high reliance on gas as the reason why we were the worst hit by the crisis in Western Europe. But the costs of poorly insulated homes started to accrue well before 2022, and the UK has long been viewed as ‘the cold man of Europe’.

Government statistics reveal that in 2010, when the Conservatives came into power with David Cameron, just 15% of homes in England reached the Government’s target level for energy efficiency. In 2022, that figure had reached almost half (45%). The Government claims this is as a result of action over their 13 year leadership, but does the evidence stack up?

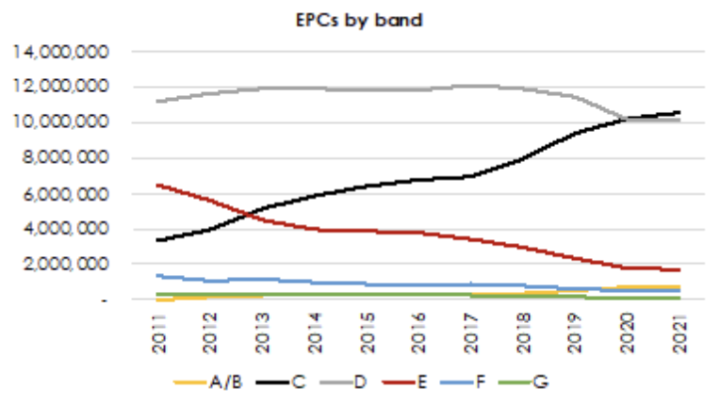

The Government has a target for as many homes as possible to reach Energy Performance Certificate (EPC), a measure of the home’s energy performance based on bills, band C by 2035. The EPC scale runs from A-G and currently the average UK home is at band D.

Firstly, there is a crucial point to consider. Created in 2007, EPCs are only required when a property is being sold or rented out, so it can be many years – decades, even – before a property gets a fresh EPC, even if extensive renovation works have been carried out. So there will always be a lag from when work is undertaken to it being reflected on an EPC.

Linked to this, new build homes are more likely to have a higher EPC due to tighter standards in Building Regulations (more on that below) and more modern appliances being installed as standard. These new homes are almost always sold onto buyers, generating an EPC, and so skewing the data so that it looks like a higher proportion of homes have a higher EPC rating.

This being said, the scrapping of tighter new build standards under the Zero Carbon Homes policy, which was pulled at the last minute in 2016 in response to housebuilder lobbying, means that the rollout of more energy efficient new homes has been slower. Indeed, at least 1.3 million new homes have been built to lower standards since 2016 due to the cancellation of the policy.

Overall, installations of insulation under Government schemes have dropped dramatically

It’s true that since 2010, Government schemes have installed around 7.7 million insulation measures into homes and there is no denying the upward trend in homes rated EPC band C, mainly because of falls in homes rated EPC bands E and D.

But the bulk of measures, around 5.5 million, were installed between 2010 and 2013 under schemes like the Carbon Emissions Reduction Target (CERT) and Community Energy Savings Programme (CESP). But these were introduced in the previous Labour Government, and only ran until 2012 because funding was pulled in 2013 when then-PM David Cameron instructed officials to “cut the green crap”.

The industry never really recovered, and in 2022, despite the gas crisis sending bills soaring, a record low of around 80,000 measures were installed in total under Government programmes – even lower than when coronavirus lockdowns limited access into people’s homes.

The data collected for 2023 so far is incomplete, but every indication is that the number could be even lower, with many experts heralding the last two years as crucial missed opportunities to lower bills and improve energy security while gas and electricity prices remain high, largely as a result of the war in Ukraine.

Installation of heating systems under Government schemes follows a similar trend. From around 170,000 heating measures like gas boilers being installed in 2013 to just 40,000 in 2022, it is apparent that there is a strong pattern of decline in measures being installed into people’s homes as part of government schemes.

What does the data tell us about insulation?

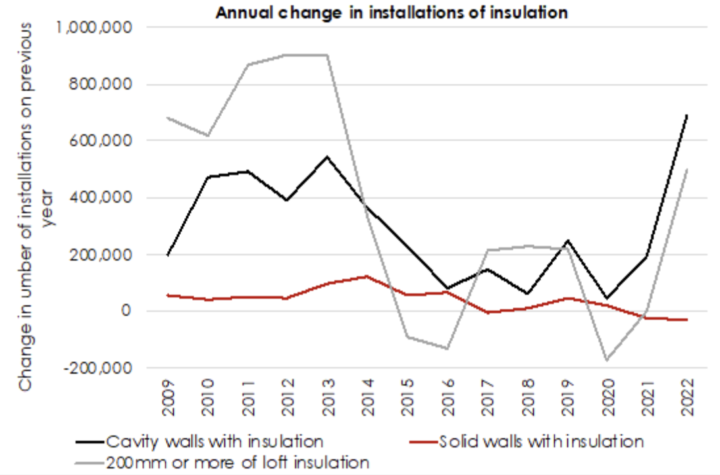

Between 2008 and 2013, around 420,000 homes received cavity wall insulation each year on average but after 2013, insulation rates fell by around half to just 230,000 homes.

Similar trends are seen for solid wall insulation, which tends to be in older homes that are more difficult to treat. Around 60,000 homes were fitted with insulation each year on average prior to 2013, but just 30,000 per year afterwards. Although it is particularly alarming that in the most recent years, solid wall insulation rates have dropped off a cliff, with just 4,000 homes receiving solid wall insulation on average per year since 2017.

However, the story is even worse when it comes to loft insulation. Prior to “cutting the green crap” around 800,000 homes were fitting loft insulation per year on average. But post that, just 125,000 homes were; a fall of around six times.

So it’s little wonder that the UK is seen by many experts as the “cold man of Europe”. Our insulation rates are low and fell sharply after schemes were scrapped, plateauing in the 2010s with cavity and loft insulation only seeing significant increases in 2022 when energy costs were higher than ever and energy security at the top of the agendas of both major political parties. The evidence points to the building regulations lag as the primary reason for the wider trend in English EPC improvement, rather than insulation coming from Government schemes since 2013.

And what about heating?

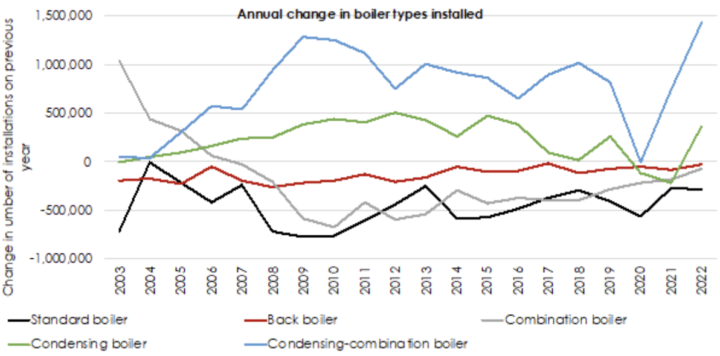

Over the years, there has been a slow but steady evolution of boilers. Following implementation of Building Regulations Part L1B for existing homes in 2005, the installation of non-condensing boilers was prohibited. There have been subsequent revisions of the Building Regulations in 2006, 2010, 2013, 2016 and 2018 too, which have impacted the types of boilers being installed, such as the 2018 Boiler Plus policy which requires boilers to have a minimum efficiency of 92%.

This caused sharp increase in the number of condensing boilers and condensing-combination boilers being installed from 2003, the latter of which eliminate the need for a water storage tank. These regulations have clearly made a difference as since 2003 sales have increased hugely, to around 1.5 million of the 1.6 million boilers sold in 2022 being condensing-combination.

However, when it comes to the improvement of EPCs over the last few decades, it is important to note the lag between when new regulations were implemented and when boilers are actually replaced. It is unlikely that many non-condensing boilers would be replaced before they broke, so the older, less efficient models may persist for many years despite not being as efficient as the modern systems.

Therefore a lag between the revisions of boiler requirements as part of Building Regulations may explain the upward trajectory in EPCs rather than the heating systems being installed as part of Government schemes.

Lessons could be learned from this boiler transition. The Government has an aim to phase out the sale of new fossil fuel boilers by 2035, with electric heat pumps the frontrunner to replace them. So far, there are no regulations that require heat pumps in existing buildings but new homes are expected to start installing them as part of the Future Homes Standard, which comes into force in 2025.

There is a £7,500 Boiler Upgrade Scheme grant available for retrofitting a heat pump into a home, but it remains to be seen whether this will be enough to drive installations up to the Government’s target of 600,000 heat pumps per year by 2028.

What else has impacted energy efficiency of homes?

Similarly to boilers, in 2010 Building Regulations were revised to mandate a U-value (essentially a measure of heat loss) of 1.6 Watts per square metre per 1C (W/m2/K) for windows. The revision was a legacy action from Gordon Brown’s Government, with Conservative Cameron inheriting the move when he came into office in 2010.

The regulation has resulted in many windows being replaced with more efficient ones, again with a lag between its implementation and the changes to the home, as the windows may be installed at any time as part of a wider renovation that does not require a new EPC.

In addition, since 2018 there have been Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards in place for the private rented sector. The MEES ban properties rated EPC F or G from being let out, although there are exemptions for properties where it would be unaffordable or impractical. This regulation is likely to have caused improvements in many privately rented properties, however tightening of the policy, which would have ensured that all privately rented homes meet EPC band C by 2028, was recently scrapped by the Prime Minister Rishi Sunak.

The Feed-in Tariff was also introduced in 2010, after being proposed and consulted on during 2009, which incentivised the installation of solar photovoltaics onto people’s roofs by offering a set price for any electricity sold back to the grid. This scheme was popular, but was brought to a close in 2019, when Theresa May was PM. Solar panels positively impact an EPC as they lower the electricity bills of the home.

Prior to this, in 2009 the EU issued a directive that aimed to phase out the use of inefficient lighting in homes, by replacing older bulbs with LEDs. Since the UK was in the EU at the time, the Directive was applied here, and led to improvements in the energy performance of people’s homes.

Likewise, the purchase of more efficient white label goods like TVs, ovens, fridges etc has also impacted EPC scores positively as their efficiency has risen over time. Prior to Brexit, the EU’s Ecodesign labelling scheme indicated the relative efficiencies of different white label goods with a simple A-G rating system, but since January 2021, the UK has had its own labelling convention, which is very similar to the EU’s.

Changes to methodology

Changes to EPC methodology’s underlying calculations, known as Standard-Assessment Procedure, were also undertaken in 2018. Revised U-values (heat loss) were implemented for all insulation types, meaning that some homes were automatically upgraded to a better EPC band despite not having any insulation work carried out. Indeed, 12% homes moved up to EPC C or above between 2018 and 20221, the equivalent of 3.5million homes, when the data shows that only 140,000 homes per year were upgraded by government schemes in the same time period.2

One consistent criticism of EPCs is that they are based on the energy bills of the home, which are largely impacted by the heating system in place. Due to the unit prices of electricity being higher than gas, this can sometimes have the perverse impact of decreasing a home’s EPC when a more energy efficient system, like an electric heat pump, is put in place of a gas boiler.

The Government has committed to reforming the EPC system so that EPCs are more accurate and up to date. Proposals include keeping a digital log of works carried out under different owners, so the assessor has a better sense of what has been done to the property, requiring more evidence about why the assessor has made certain assumptions, and adjusting the calculations so that running costs are not weighed too heavily compared to emissions or efficiency. For example, experts have called for reform so that installing a heat pump does not negatively impact an EPC.

All in all, it is true that the energy efficiency of homes is improving, and a good thing too as energy prices are predicted to remain high, while gas market volatility means that we are not out of the woods in terms of energy security yet either. But the data shows that this is not down to progress under Conservative leadership or policy. Indeed, without getting back on track, particularly when it comes to insulation, there is a real risk of progress flatlining altogether.

Share