The GGR Independent Review: what does it say?

Our analyst has digested all 200 pages of the Greenhouse Gas Removals (GGR) independent review to break down this significant moment in the removals discussion in the UK.

By Tom Cantillon

Share

Last updated:

Coming in at 200 pages, the GGR review is a comprehensive review of the state of GGR in the UK, readiness of various GGR technologies, and barriers to scaling removals to deliver on the UK’s net zero ambitions.

What’s the background to the review?

In May 2025, the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) commissioned an independent review of GGRs to understand how different GGR options, such as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), afforestation, and direct air carbon capture and storage (DACCS) can assist the UK in meeting its 2050 net zero target.

Removals are required to realise the ‘net’ in ‘net zero’ as even with significant emissions reductions across the economy, some industries will have residual emissions that are unable to be abated (e.g. emissions from ruminant agriculture). Removals help balance these emissions and limit the damaging impacts of climate chance.

The review was chaired by Dr. Alan Whitehead CBE, and was published in October 2025.

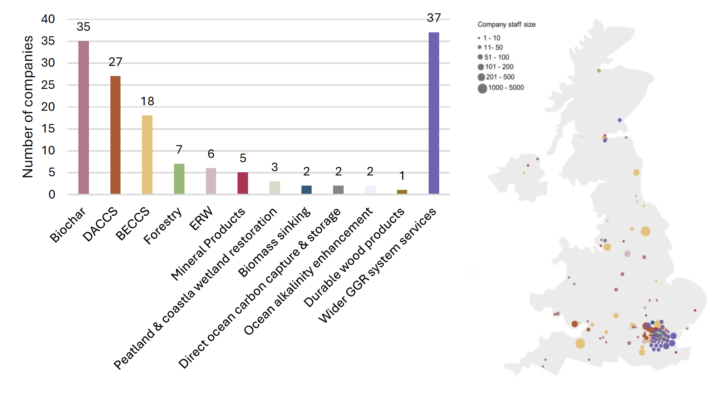

Chart and Map of UK GGR companies, according to GGR solution and staff size (2000-2024)

What does the Committee on Climate Change say about GGR?

The Committee on Climate Change’s (CCC’s) advice on the Seventh Carbon Budget recommends emissions be compensated on a source-sink symmetry basis – i.e. that biological emissions be balanced with biological removals, and fossil emissions be balanced with engineered (novel) removals, often with geological storage – currently limited to BECCS and DACCS.

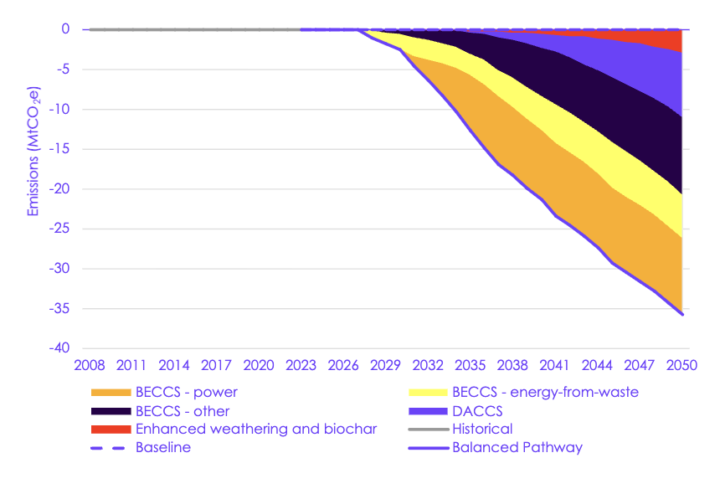

In practice, this means that residual emissions pertaining to agriculture and land use will be compensated for through conventional CDR, primarily afforestation and grasslands, with -29.9MtCO2e of removals in 2050. Residual emissions from all other sectors, primarily aviation, will be compensated for through novel CDR methods, primarily BECCS, DACCS, biochar and enhanced rock weathering (ERW), with -35.8MtCO2e of removals in 2050.

Sources of abatement in the balanced pathway for engineered removals

What are the headline recommendations?

The report makes five headline recommendations to government to ensure GGR deployment meets Carbon Budgets. These are.

- The government should develop a GGR Strategy to outline the contribution of GGR to meet carbon budgets and its net zero target.

- The government should establish an Office for Greenhouse Gas Removals to enhance coordination on GGR policymaking and project deployment.

- The government should minimise the use of imported biomass feedstocks in its GGR deployment.

- The government should amend and rename the SAF Mandate to become a Net Zero Aviation Mandate, driving procurement of both sustainable aviation fuel and GGRs.

- The government should position the UK as a leader on GGRs in international climate cooperation, making use of the UK’s comparative advantages in science and technology, storage potential, and financial services.

What GGR technologies does it recommend?

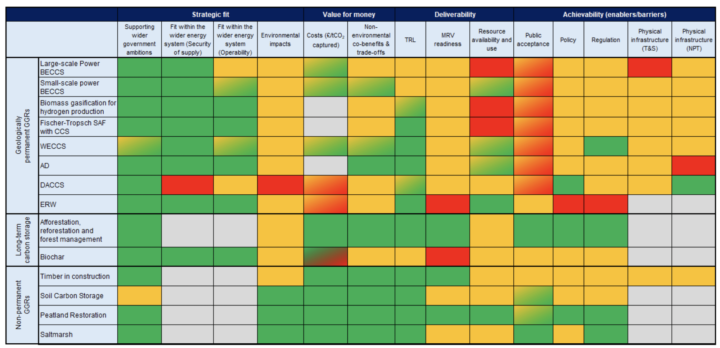

A key framing in the report is that no one GGR technology is a silver bullet, and that the UK government will need a mosaic approach to technology deployment, spanning:

Geologically permanent removals that store CO2 for thousands of years, including BECCS, DACCS, and waste-to-energy with carbon capture and storage (WECCS) – capturing CO2 from household rubbish.

Long-term carbon storage that stores CO2 for hundreds of years, including afforestation and biochar.

Non-permanent removals that provide shorter-term storage, often with co-benefits. This includes things like peatland restoration, soil carbon storage and using timber in construction.

The review emphasises source-sink symmetry by advocating for ‘geological net zero’ requiring emissions from fossil fuels to be balanced with geologically permanent removals.

What are ‘low regret’ options for GGR deployment?

While the Review does not outline specific deployment levels of different GGR technologies, it does highlight approaches that are ‘low regret’. This is defined as technologies that have limited costs and barriers, deliver benefits beyond CO2 removals, and contribute towards wider UK government ambitions.

The low regret options in the report are:

Geologically permanent solutions based on UK sustainable waste feedstocks with CCUS. This would include applying carbon capture and storage technologies to waste treatment solutions, such as anaerobic digestors, energy-from-waste plants, and small-scale plants using waste as feedstocks. This could include the use of biomethane and SAF to displace fossil fuels.

Geologically permanent BECCS based on sustainable biomass feedstocks that do not compete with food production. This would include BECCS and anaerobic digestors using domestic residues from agriculture and forestry as well as slurry.

Long-term carbon storage solutions with significant co-benefits. This would include woodland creation, and potentially biochar, if its measurement, reporting and verification (MRV) becomes sufficiently developed.

Non-permanent GGRs with low costs and/or significant co-benefits. This can include soil carbon storage, peatland restoration, saltmarsh restoration and the use of timber in construction.

Notably, DACCS and enhanced rock weathering (ERW) are not currently considered low regret by the report. For DACCS, the Review is concerned by its high costs of deployment, alongside the high energy usage of DACCS plants. This could be overcome via exploring waste heat-to-energy sites or deploying DACCS when surplus renewable energy is being generated. For ERW, the Review believes it could become a low regret option once advances are made on MRV, regulation and policy.

‘Low regret’ deployment options for the UK

Who pays for GGRs?

Transitioning the UK to a net zero economy and society will incur costs, both to finance the transition, and lost revenues from phasing out emitting activities (e.g. fuel levies). A recent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) report estimates this to be £116 billion, over 25 years1. However, not reaching net zero also incurs costs, as the impacts of a warming world hit the economy. In a three-degree warming scenario, this is estimated to reduce GDP by 8% in 2070 and increase public sectoring borrowing to cover climate damages to over 4% of GDP. Taken together, the OBR report highlights that the costs of not achieving net zero outweigh the costs of achieving it, from a mitigation perspective. Costs and benefits associated from adaptation were not considered.

A key question the Review grappled with was who should provide the funding needed to support the deployment of GGRs in the UK. It considered financing in the context of the UK emissions trading scheme (ETS), the SAF mandate for aviation, the voluntary carbon market, and the potential for procuring GGRs internationally.

GGRs and the UK ETS

The government has previously indicated its intention to expand the coverage of the ETS to include energy from waste and domestic shipping, as well as include engineered removals. Decisions around woodland creation’s inclusion have not been taken but, as the Review notes, its inclusion would have issues, not least increasing misalignment between the EU ETS, with which negotiations to link the two schemes is ongoing.

Inclusion of GGRs in the ETS can provide financial incentive for their deployment at the level of the ETS price. However, without a significant increase in the ETS price, the government would be forced to ‘top up’ the payment to the costs of GGR deployment, given the current high costs of GGRs. Absent any alternative funding mechanism, this cost would be borne by the taxpayer.

The review notes that two policy options are available to avoid this – either constrain the supply of allowances sufficiently so that the gap between the ETS and GGR deployment prices are minimised, or employ a sub-mandate, whereby participating entitles are obliged to pay for an increasing fraction of GGR deployment over time. A buy-out price would also need to be set to ensure compliance with payment into the sub-mandate.

Woodland in the UK ETS

The Review agrees with the analysis of the CCC that including woodland creation in the ETS would be inappropriate, given it would allow fossil emissions to be balanced with biological removals, which goes against the concept of geological net zero. However, the Review acknowledges that additional financing is required to scale woodland creation sufficiently. Given this, the Review suggests two policy mechanisms for financing woodland creation via the ETS:

Funding woodland creation with ETS revenues e.g. a portion of ETS revenues would be earmarked to finance woodland creation. Such hypothecation is not a popular policy option in the UK Treasury but is used in a variety of instances including Vehicle Excise Duty (VED) and the Landfill Tax.

Funding woodland creation via a sub-mandate in the ETS. As described above, participants in the ETS could be required to pay an increasing fraction of the costs associated with woodland creation.

Aviation and the SAF Mandate

Aviation is projected to be the industry with the highest emissions in 2050. Under the CCC’s balanced pathway for net zero, it is assumed that aviation will pay for the removals necessary to balance their residual emissions, as SAF and demand-side abatement alone is insufficient to deliver net zero aviation. Given recent government decisions on airport expansions, the Review acknowledges that demand side reductions are increasingly unlikely, leaving GGR and SAF deployment the most viable policy options.

Currently, the SAF Mandate obliges suppliers of aviation fuels in the UK to include in their output a rising proportion of SAF, from 2% in 2025, to 22% in 2040. As SAF has lower emissions than kerosene, SAF represents an emissions saving, rather than actively reducing atmospheric emissions associated with aviation.

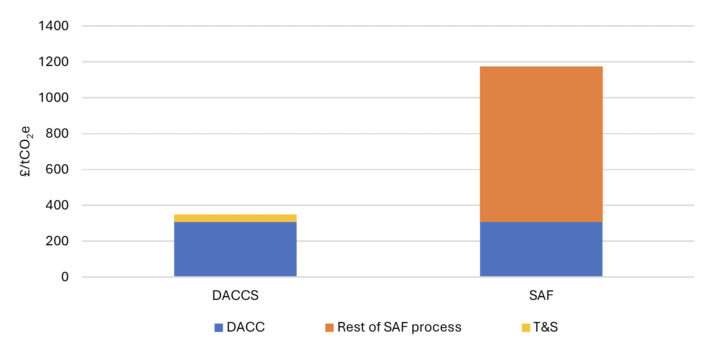

Given this, and the need to scale up the removals necessary to balance aviation emissions, the Review recommends expanding the SAF mandate to become a Net Zero Aviation Mandate, increasing the proportion of emissions to be addressed by SAF and GGRs combined. The Review views this as a means of reducing taxpayer liability for funding GGR deployment, avoiding competition for similar feedstock (in the case of biomass for BECCS and SAF) and, potentially, allowing for more cost-effective abatement, particularly where GGRs prove cheaper than SAF production.

Comparison of £ per tCO2e abatement costs of DACCS and SAF

What about sourcing GGRs internationally?

The CCC has consistently avoided recommending the usage of international mechanisms, such as carbon credits, to achieve the UK’s net zero ambitions, and the Review is no different. The Review finds that sourcing GGRs internationally carries significant risks and impacts, particularly around ensuring project integrity and the risks of impacting global fair burden sharing and the UK’s perceived international leadership on climate action.

However, the Review does find a potential role for international cooperation for DACCS, given its high deployment costs. Although the UK’s relatively clean electricity grid means it could produce DACC removals at a lower cost than other countries, in the longer term it may be the case that DACC removals become cheaper than in the UK, particularly in ‘sunbelt’ countries with high potential for solar energy generation. In these cases, it may be prudent to establish bilateral agreements for building GGR projects abroad, where the UK would secure access to lower cost DACC removals. The Review notes this should not be done at the expense of the UK’s current relative advantage in developing scaled GGR.

What about biomass?

A key debate in the GGR space is the role that biomass, particularly biomass utilised in BECCS, should play. BECCS deployment is limited by feedstock (input) availability, including waste feedstock, but also the growth of energy crops such as willow and miscanthus for BECCS. For the latter, this raises questions around land-use, with increased energy crop production reducing the amount of land available for other activities, such as food production or nature restoration. With current large-scale bioenergy plants in the UK running on imported forestry residues, shifting to energy crops is a live issue.

The Review takes a cautious approach to biomass feedstocks, emphasising the need for the UK to demonstrate leadership in sustainably sourcing biomass. To that end, the review calls for the publication of Defra’s Land Use Framework, to understand future land availability in England, and guide decision makers, from landowners to local councils, in making effective land use decisions. Additionally, the Review recommends limiting imported biomass as much as possible to reduce global land-use pressures.

What are the co-benefits of GGRs?

Greenhouse gas removals have a range of co-benefits, depending on the technology in question. The Review highlights a number of these.

Engineered removals can create economic activity and jobs, thereby contributing to the government’s growth objectives. This can happen throughout their lifecycle, from innovation, through operation, and the potential for their outputs (e.g. carbon dioxide) to be used in other industries and sectors. The Review estimates the global GGR market will be up to $1.2 trillion by 2050, with the UK well placed to capitalise on this opportunity, given its relatively well-developed policy on GGRs and storage potential in the North Sea. The Review highlights that these economic opportunities are largely concentrated in industrial centres for engineered removals, while land-based GGRs can lead to economic opportunity for rural areas, and represent new job opportunities to farmers in livestock agriculture or to rural workers.

GGRs can additionally provide access to low or zero-carbon energy in their deployment, via technologies like power BECCS (producing electricity from biomass while capturing and storing the carbon) or the generation of hydrogen or SAF with carbon capture.

For land-based GGRs, the Review highlights the contribution they can make to environmental objectives, such as enhanced flood resilience, improved soil health, biodiversity gains, erosion control, and physical and mental health benefits via access to nature. GGRs can therefore contribute to other government objectives, such as their Environmental Improvement Plan targets, while removing carbon from the atmosphere.

What next?

Key actions to lookout for mainly revolve around the degree to which the government accepts, acts on, or even acknowledges the recommendations contained within the report. Regardless, the report places additional pressure to follow through on already announced policy areas, such as the Land Use Framework, and the sustainable biomass framework consultation. The recommendations around the SAF mandate and aviation may prove more complicated in the context of the recent airport expansion announcements, although the government has approved these whilst remaining committed to net zero, increasing the need for direct mitigation of higher emissions.

Regardless, the challenge around responsibly scaling GGRs will not go away given the need to limit the damaging effects of climate change by reaching net zero. The question is how proactive the government will be in driving the agenda and realising the economic and wider benefits that investments in GGRs can provide.