Climate and food: home and away

As UK harvests of key foods fail, ‘back-up’ imports wobble under climate-driven extremes, threatening our food security

Last updated:

Extreme heat of the last year combined with the extreme wet winter just gone mean harvests of many traditional crops that we take for granted including potatoes, onions, sugar beet and wheat are down in the UK. But at the same time, imported ‘back-up’ supplies that could fill shortfalls are also being hit by weather extremes. As these extremes worsen with climate change, we are starting to see examples of where neither homegrown produce or imports can necessarily be relied upon to meet the UK’s food demands which can lead to price increases and, or shortages.

In the United Kingdom, we import 40% of the food we eat (NB - at the time the report was published, the number was nearly half). Around half of that is made up of commodities we do not grow here, with a similar proportion coming from climate impact hotspots. In 2023, we imported 36 billion kilograms of food, with a value of £61 billion.

Imports

17% of these imports came directly from nations with low climate readiness, i.e. those that are not only exposed to climate impacts, but also lack the capacity to respond and adapt to them. A quarter (25%) came from Mediterranean nations, many of which have been experiencing historic heat and drought linked to climate change for the past few years.

As climate impacts become more frequent and intense, our food supply chains are ever more vulnerable. 2023 was the hottest year on record, with previous high temperatures surpassed on both land and sea to increasingly dangerous effect. Extremes of heat, cold, drought, flooding, fire and storms have harmed food crops everywhere.

Growing at home

When imports are threatened, discussion in the UK can turn to the importance of becoming self-sufficient, i.e. to growing more of our food at home, and cultivating threatened products here instead. For many foods – such as cocoa, bananas and coffee – this is implausible, as these crops require a tropical climate and therefore cannot be grown at commercial scale in the UK.

But for many foods – such as some cooking oils, vegetables like potatoes, cauliflowers and onions, and even sugar – they can be grown in the UK. However, these crops are seasonal, meaning we rely on imports to meet demand when UK conditions are unsuitable for growing. The problem is that climate change is now threatening the production of these foods both at home and overseas.

This year, the UK’s wet winter, which scientists have said saw rain made 20% heavier by climate change, had a disastrous impact on agriculture as record wet conditions delayed planting and caused crops to rot underwater. ECIU research has estimated this decline in output could reduce headline self-sufficiency across all UK farming sectors from 86% to 78% (when measured by volume), with arable farmers facing losses of nearly a billion pounds as a result. Harvests are generally getting earlier due to climate change, but the wet spring and summer that have followed are likely to delay harvest of cereals like barley and oilseed rape, further impacting supplies.

Overseas, our suppliers of the same crops are also being battered by climate impacts. Countries in western Europe, like Germany and France, (which supply onions and wheat) have been exceptionally wet, grappling with flooding, while much of southern Europe and North Africa are experiencing yet another year of devastating drought. Scientists have said July 2024’s extreme heat in the Mediterranean would have been impossible without climate change, which made temperatures 3.3°C hotter. Agriculture everywhere is impacted, limiting supplies that consumers could see in rising prices. Here, we highlight some key British foods threatened in both the UK and overseas.

In addition to climate extremes threatening crop yields, in recent years volatile oil and gas prices have added to the problem. With some foods – like tomatoes, for instance – we grow some in the UK for part of the year. Doing that under glass or in polytunnels can increase our ability to produce more of these in the UK, including in colder times of the year. However, soaring costs of gas after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine made the cost of energy for heating indoor crops prohibitive for many. Continued reliance on fossil fuels for heating into the future, could well see a return of that problem for farmers and food producers.

Prices and food security

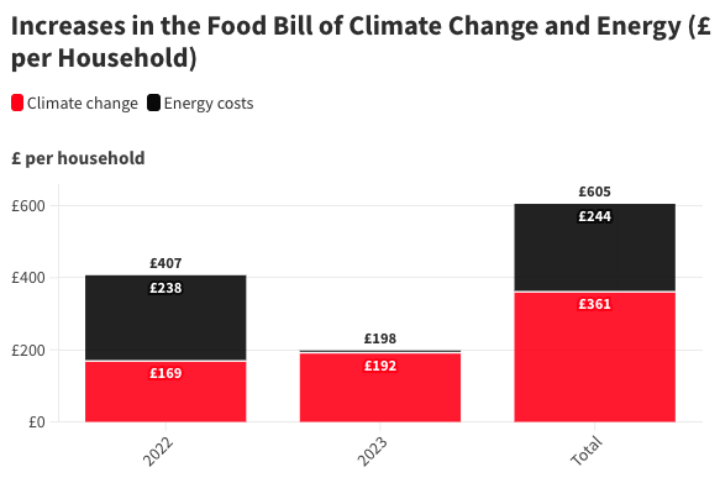

All of this is feeding through to consumers. From the start of 2022 to the end of 2023, climate change added £361 to the average household food bill. This number is likely to have increased given the impacts we’ve seen in the first six months of 2024 alone.

But on top of price rises, impacts hitting some of the same staple foods at home, and overseas, means that our future food security is put under ever greater strain, as climate impacts worsen. Within the first week in office, Steve Reed, the new Secretary of State for the Environment, has outlined improving food security as one of his department’s top priorities. Climate impacts are making it clear that this cannot be addressed without measures to mitigate and adapt to climate change; identified by the previous government as one of the biggest threats to food production in a 2021 report.

Solutions

There are two clear, currently available solutions to averting threats to food security posed by climate change: mitigation and adaptation.

Mitigation means cutting emissions – limiting further warming to avert even worse and more dangerous impacts into the future. Net zero emissions by mid-century is the aim signed up to by almost every country on the planet, in the Paris Agreement. If achieved, including by halving emissions this decade to get on track, then it can still limit temperature rises to 1.5°C. But the world is currently still on track for between 2.5°C and 3°C of temperature rises above pre-industrial levels. Despite considerable global momentum, driven by investment from the world’s biggest emitters – most notably China, which is also the world’s biggest investor in clean energy, but also the EU and the US which seek to compete with China – the world is not yet on track towards net zero emissions by mid-century.

Adaptation is already needed at 1.2°C of temperature rise, as we can see from the impacts on food crops, the shortages and price rises, and the damage done to livelihoods of food producers around the world. It will only be needed more, as temperatures rise, but the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is clear that there is a limit to our ability to adapt. This is why we need both emissions cuts, and adaptation to more dangerous climatic conditions. Food security is an issue for every nation, but it hits hardest for the poorer nations – which are also those most likely to be hit by the worst climate impacts, harming agriculture and food production sectors. Wealthy nations will need to provide support to farmers at home, and abroad, in order to adapt and secure our food supplies.

At home, that means programmes like ELMS – Environmental Land Management Schemes – to support farmers to develop more sustainable and resilient methods that can better cope with extreme heat, drought and rainfall. Overseas, it means providing funding via international climate finance (ICF) to fund adaptation programmes, such as to provide technical assistance to small and marginal fruit and vegetable farmers in Bihar, one of the poorest parts of India, or to strengthen resilience amongst climate-vulnerable sectors like horticulture and agriculture in Kenya. It also means providing overseas development assistance (ODA) to aid recovery from climate disasters, and support to facilitate UK companies investing overseas, via UK Export Finance.

Examples of threatened crops

Though we’re only halfway through the year, overseas we have seen cocoa battered by extreme heat and erratic rainfall in West Africa (bumping up the price of everyone’s Easter eggs), extreme drought in the Amazon basin desiccate banana crops and the price of coffee surge due to extreme heat in Vietnam and Brazil, to name but a few examples. But with flooding and extreme heat in producer nations overseas, and the wettest winter on record here at home, some supermarket staples are being hit from both sides.

Values are for the last year of available data. For some crops this is 2022, for others 2023.

COOKING OILS (rapeseed and olive)

UK | In 2023, the UK produced over 1bn kg of rapeseed (used to make vegetable oil for cooking). We were 63% self-sufficient.

UK yields of oilseed rape, which is used for domestic and commercial vegetable cooking oil, are projected to be as much as 38% lower this year compared with 2023, after the extreme wet weather in winter and early spring hit crops. Compared to the average yield since 2015, the reduction could be as much as 54%. The UK’s wet winter was made 20% heavier by climate change.

IMPORTS | In 2023, we imported 62m kilograms of olive oil worth £332m. Almost all (89%) came directly from the Mediterranean region (55m kg worth £299m). Nearly two thirds (61%) came directly from Spain (39m kg worth £192m) and a fifth (19%) came directly from Italy (12m kg worth £79m).

Olives, principally grown in the Mediterranean, have been hit by extreme heat over the last few years that would have been impossible without climate change. Harvests have fallen sharply as some trees failed to fruit when flowers were literally burned away. As supplies have fallen, prices have soared.

Historic drought has hit Spanish production for the second year running. Olive oil is now the most shop-lifted product in Spain, with the price there having risen 272% since September 2020. This June, Italy’s national statistics bureau stated that Italian production of woody crops including olives was down 11.1% last year due to climate change.

In the UK, we paid £33m more for 17m kg less olive oil imports in 2023, compared with 2022. The average consumer price stood at £8.46 a bottle in May 2024, up 42% on the price a year before and over 100% higher than two years ago. Olive oil currently boasts the sharpest increase of any item in the ONS consumer price inflation basket of indicators.

ONIONS

UK | In 2022, the UK produced almost 319m kg of onions. We were 47% self-sufficient.

Onions require sun and dry weather; excess rain or flooding can ruin crops. Once harvested, they are ideally dried in the sun; excess rainfall can limit this. Elevated humidity can also cause fungal and bacterial development on the onions.

The wet winter of 2023/2024 prevented or delayed onion planting. This is evident in the statistics, with DEFRA data for 2023 showing that onion volumes were down by 13% and production area down by 3.6% year-on-year.

Additionally, climate change is exacerbating the disease fusarium basal rot (FBR) that decimates onion crops as it prefers warm, wet conditions. Warwick University unveiled a project to combat the disease earlier this year.

IMPORTS | In 2022, we imported 335m kilograms of onions worth £191m. Nearly two fifths (37%) came from the Mediterranean, i.e. 20% from Spain, 11% from Egypt and 6% from France.

The Mediterranean has been experiencing severe and prolonged drought for the past few years. Scientists have said this would have been virtually impossible without climate change.

Though onions prefer dry conditions, heat stress harms their development and can lead to smaller crops. The drought, which continues to persist this year, affected Spanish onions in 2022 and 2023.

Over the past year, there has been an onion crisis in several countries. For example, Tanzania restricted exports to neighbouring Kenya, which was unable to make up the shortfall itself due to extreme drought linked to climate change, causing prices to triple.

SUGAR

UK | In 2023, the UK produced over 1bn kg of sugar. We were 54% self-sufficient, as we produce half of what we consume from domestic sugar beet and import the other half as cane sugar from tropical countries.

Sugar beet has been another victim of the UK’s wet winter, made 20% heavier by climate change, with crops rotting in the ground due to intense rain and flooding.

IMPORTS | In 2023, we imported 1bn kg of sugar worth £588m.

We paid more for sugar imports in 2023 than 2022, with the average price per kilo going up 32% in a year.

This is partly because extreme heat and drought hit key sugarcane producers India and Thailand in 2023 and 2024. Although we don't import directly from them, like many commodities, sugar is traded on international markets so this pushed prices up for UK consumers as well.

For example, according to ONS figures, the price of white sugar has risen nearly 68% for UK consumers over last two years to £1.19/kg.

CAULIFLOWERS AND BROCCOLI

UK | In 2022, the UK produced almost 149m kg of cauliflowers and broccoli. We were 55% self-sufficient.

Brassicas do not like extreme wet, and very wet summers can devastate harvests and drive shortages and price rises. In the UK in 2019, a very wet summer severely harmed cauliflower crops and the shortages caused three to four-fold price increases.

More recently, the UK’s wet winter of 2023/24 decimated various vegetables including broccoli and cauliflower, leading to a ‘nationwide shortage’ before Christmas. Heavy rains delayed planting and caused crops to rot in the ground. Such disruption is evident in the statistics. The wet conditions meant that the planted area of brassicas decreased by 3.1% to 23,000 hectares in 2023, leading to a 0.4% fall in broccoli yields and a 9.2% year-on-year fall in cauliflower volumes.

IMPORTS | In 2022, we imported 121m kilograms worth £176m, 93% of which were from the Mediterranean (112m kg worth £151m). 80% came directly from Spain alone (97m kg worth £128m).

Brassicas prefer cool, damp weather. In extreme heat and dry conditions, such has been seen in Europe over the past few summers, they tend to ‘bolt’ or form small or deformed heads. This can mean crops are of lower quality and volume, affecting supply.

Half of the broccoli and cauliflowers we consume are imported. More than 90% of them come from the Mediterranean, a region that has been experiencing severe and prolonged drought for the past few years that would have been virtually impossible without climate change. Spain, our top supplier, has experienced historic drought since the start of 2024.

WHEAT

UK | In 2023, the UK produced almost 14bn kg of wheat. We were almost 97% self-sufficient.

The UK’s ongoing wet weather delayed planting of winter wheat last year, ruined much of the crop that farmers did manage to plant and delayed spring planting as well. ECIU research suggests this could decrease our self-sufficiency by almost a quarter, while in late May a spokesperson from the NFU predicted losses of 25% of UK wheat this year.

IMPORTS | In 2023, we imported almost 2bn kg of wheat worth £456m. Germany and France were two of our top suppliers.

Like the UK, other countries in Western Europe had a wet winter and spring like. Germany, France and Italy were hit by heavy rainfall and storms that affected winter wheat (planted in autumn 2023) and delayed the planting of spring wheat. The situation was particularly bad in France, Europe’s biggest wheat producer, where the ‘non-stop’ rain decimated yields and affected quality. Wheat in the north of Italy was hit by storms, while in the south it was affected by drought, adding further strain to the market.

The AHDB said in June that the global wheat outlook is likely to have a tighter balance next year (2024/25). Despite the modest increase in US production and a drop in global feed demand, bad weather across the EU and Russia so far this year has created substantial losses. This is likely to push prices up for consumers.

POTATOES

UK | In 2023, the UK produced almost 3bn kilograms of potatoes.

The UK’s relentless wet weather, that started last year, delayed harvesting, caused crops to rot in the ground and delayed planting, leading to a shortage of UK-grown potatoes before Christmas. Farmers continue to struggle this year. In April, one major retailer said that the wholesale price of potatoes was up 60% year on year, but so far only half of that was being passed onto consumers. ONS numbers show the price of potatoes rising 54% over the last two years in the UK to 88p/kg in May this year.

Scotland is a major grower of seed potatoes (potatoes grown to produce more potatoes), accounting for 75% of the planted area in Britain. Historically, the cool, wet climate has kept potato viruses at bay, as these conditions are not favourable for the aphids that transmit them. Such disease-free conditions grant Scottish seed potatoes ‘high health’ status. However, as the climate warms, aphid numbers are increasing and so is the risk of disease.

IMPORTS | In 2023, we imported 80m kilograms of fresh potatoes worth £42m. Over a tenth (11%, 9m kilograms worth £4m) came directly from Egypt.

Egypt is a major importer of Scottish seed potatoes, buying 59% of UK exports in season 2022-23. They then grow potatoes for consumption to export to other countries, which includes the UK. Studies have predicted that climate change could result in a 13% decrease in potato yield in Egypt, largely due to a lack of water. Egypt is currently experiencing extreme heat that is causing major disruption to daily life.

The problem with potatoes is multifaceted: if growing Scottish seed potatoes becomes more difficult due to climate change, so will production in the countries that use them. Additionally, climate impacts in those countries could threaten our imports of fresh potatoes from them, at a time when UK production is failing due to climate impacts here.

Method

Import values were calculated using the Government’s Trade Tariff data for commodity item codes and HMRC’s international trade data for commodity flows.

UK self-sufficiency for each crop was calculated using DEFRA's Agriculture in the UK data. Calculating self-sufficiency requires values for domestic production, imports and exports. For example, if self-sufficiency in a particular commodity is 50%, that does not necessarily mean imports make up the remaining 50% because exports must also be considered. Each commodity uses the most recent year of data: for some this was 2022 and others 2023.

Inflation data was calculated using the Office for National Statistics (ONS) data for the basket of indicators released in June 2024, compared to prices at the start of 2022. Between January 2022 and January 2024, the ONS has said that overall food inflation was 25%. In the year to May 2024, the overall inflation rate for food was 1.7%, down from 2.9% in the year to April 2024.

Previous ECIU food reports provide useful background information:

- Mediterranean food imports.

- Climate vulnerable nations food imports.

- El Niño and food imports.

- Climate impacts on food bills for average UK household.

- Olive oil and rapeseed oil analysis.

- Chocolate and cocoa analysis.

- Italy food imports to UK analysis.