Brexit: implications for energy and climate change

What are the implications of the Brexit deal on climate change and energy?

By Jess Ralston

@jessralston2Share

Last updated:

Ambition and targets now embedded in deal

Both the EU and UK have net zero carbon emissions targets set for 2050. This is necessary to meet the 1.5C global warming target agreed by nations in the Paris Agreement of 2015, which is the maximum temperature rise considered to be ‘safe’ before widespread impacts and risks to human health.

For the first time in a trade agreement, and perhaps setting a precedent for future deals for example with the US and China, the net zero carbon emissions by 2050 target is embedded within the text.

Specifically, the phrase ‘each party reaffirms its ambition of achieving economy-wide climate neutrality by 2050’ has many climate experts singing the praises of the deal, as a regression – going back on the net zero goal – could now result in the TCA being terminated, suspended or presumably causing tariffs to be imposed between the two trading blocs. It therefore appears that climate change and net zero is now a make-or-break issue for the success of the deal.

Actions that would constitute a breach of the deal in terms of climate change are not explicit in the TCA’s text. Although Marley Morris, an expert that recently published a report on the Brexit deal, explains that to be directly in breach of the TCA, there would have to be a renouncement of the Paris Agreement from one side, or clarity that one party is not delivering.

The TCA will put focus on targets set by both parties. This includes the 2030 emissions reduction targets for both the UK and the EU, as set out in their Nationally Determined Contributions (the commitments made by individual countries towards delivering the Paris Agreement).

In addition, the preamble of the TCA underpins action on climate ambition. It highlights both parties ‘recognise the need for…high levels of protection… [for] the fight against climate change’ and within the text there is a commitment to ‘strive to increase’ both party’s ‘climate level of protection’.

‘Climate level of protection’ is defined as meeting 2030 emissions reduction targets. In the TCA, this is stated as a 40% greenhouse gas economy-wide reduction in the EU and for the UK, meeting its share of this 40% reduction target.

However, these 2030 targets are now outdated, as both parties set out their Nationally Determined Contributions in 2020. In the UK the new target is at least 68% reduction and in the EU a 55% reduction, both on 1990 levels.

Changes to accounting, jurisdiction and future areas still to be thrashed out

Leaving the EU will bring changes in the UK’s carbon targets,progress towards them, how they have been accounted for. This has already been a factor in calculations underpinning the UK’s NDC, and will be a feature in carbon budget calculations from here on.

The Brexit deal could also give the UK more independence to regulate and legislate for a number of policy areas within jurisdictions, including climate change. Forbes has reported that the UK’s new status away from the EU-wide net zero 2050 goal ‘will make it easier’ for the UK to achieve a substantially higher ambition than the EU as it will no longer be ‘weighed down’ by some countries within the EU that are still dependent on high-carbon sources of energy, like Poland that still uses a large proportion of coal.

But there are areas of the TCA that still have not been fully concluded. The text of the deal indicates that a ‘framework for cooperation on renewable energy and tackling climate change’ between the two blocs has been agreed in principle, with further detail forthcoming.

Given the recognised importance of international collaboration of this issue – EU Commission president Ursula von der Leyen singled out energy and climate change as ‘areas of mutual interest’ – both the UK and EU are likely to want to ensure that this goes ahead.

Internal Energy Market (IEM)

The EU’s Internal Energy Market (IEM) was adopted in 1996 with the aim to ‘build a more competitive, customer-centred, flexible and non-discriminatory EU electricity market with market-based supply prices.’

Essentially, it ensures that the most electricity possible is sent from lower-priced markets to higher priced markets, all based on supply and demand in the countries taking part and making energy trading as cost-effective as possible.

When the UK left the EU, it also left the IEM. Within the TCA there are guarantees on security of energy supply and commitments to ‘facilitate continued flows of energy – essential to the functioning of both economies – by putting in place new trading arrangements over interconnectors.’ There are also commitments to establish a new ‘Specialised Committee on Energy’ and a new ‘multi-party agreement on energy’ in order to oversee tariff-free trade between the two parties in future.

This means that while there is no disruption to energy security expected, and even though both parties will work to implement the agreed model of trading in due course, there may be some impacts on the cost of energy trading. Under the deal agreed by the UK and EU, new trading arrangements for gas and power trading are to be developed by April 2022.

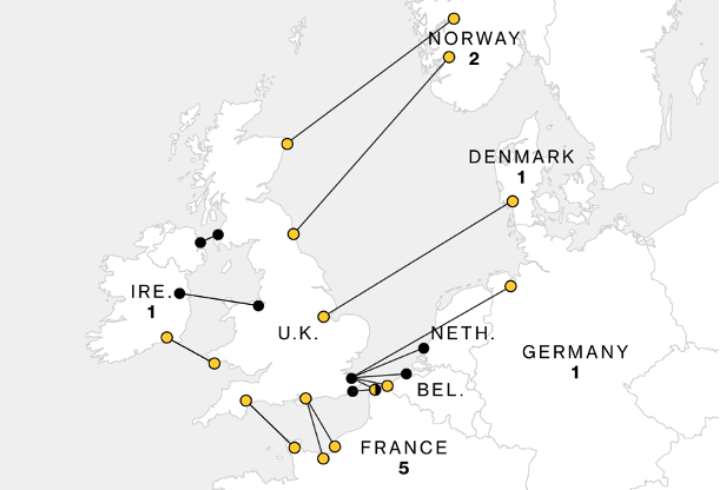

Electricity prices in Europe are generally lower than in the UK, so historically this has kept costs in the UK lower as we import this cheaper electricity. From the 1st January 2021, electricity can be traded across the interconnectors as before, but instead of a one-step process to buy and transmit electricity across interconnectors, there are now two steps as agreements to buy power and to use interconnectors have been decoupled.

The industry is hailing this as ‘additional red tape’ (such as ‘customs declarations and changes in day ahead auction procedures’) that leads to ‘increased costs of energy trading’, which will eventually be passed onto energy customers.

To this end, the London School of Economics in 2020 estimated the costs of both a ‘soft elexcit’, where the coupled system is maintained, and a ‘hard elexcit’, where the UK leaves the IEM, could vary between £570 million and £2 billion.

IEM linked to access to fishing in UK waters

The Brexit Agreement contains provisions for the deal to be reviewed every five years or if a new country joins the EU. Likely to be a part of these review discussions is access to fishing waters and the IEM.

The TCA explains that the secured and continued access to the EU energy market will only be permitted until 30th June 2026, the same exact day that the UK has given as a deadline for the EU’s access to fishing waters. Fishing was one of the most controversial issues during the negotiations and was a stumbling block for completion throughout.

As access to the IEM is so beneficial for the UK, it appears that this is ‘no coincidence’ and that both aspects of the deal will be used as leverage in ‘annual negotiations’ between both parties going forwards from 2026. According to Forbes, ‘the EU will not give the UK continued access to the energy market unless the UK continues giving access to its fishing waters.’

Product and environmental standards

Eco-design labelling

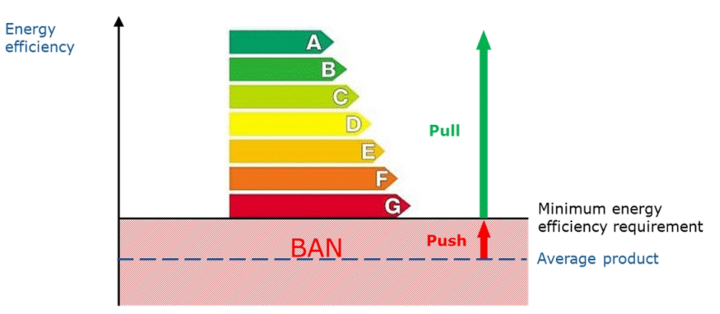

The EU-wide ‘eco-design’ standards for products was brought in as an EU Directive in 2009 and today, many items inside the home and workplace require eco-design labelling.

UK product standards post-Brexit have been highlighted as one potential issue. This is because despite promises that current green standards will not be weakened, there remains potential of a ‘race to the bottom’. Before the Referendum, product standards were highlighted as EU red tape.

However, prior to the TCA, the Government released a call for evidence and consultation on new Ecodesign and energy labelling standards in the UK after Brexit (from 1st Jan 2021). It stated that these ‘better products policy regulations’ would enable the UK to use ‘its new independence to improve its Ecodesign and energy labelling in order to maximise the benefits for UK businesses and consumers’.

This would be achieved through raising Ecodesign requirements for certain products (such as electric vehicles and washing machines) to ‘yield greater energy, resource and carbon savings’ and considering new product categories (e.g. welding equipment and commercial refrigeration) not regulated in the EU.

This could be seen as going beyond the EU’s standards and increasing the minimum standards required for Ecodesign products. While Northern Ireland will still be subject to the same standards as the EU, manufacturers now importing products to the UK will be required to meet higher standards.

There is a clause in the Brexit Agreement that meets this promise to ‘uphold environmental standards where weakening them would impact on trade or investment between the two parties’. On the surface while this may seem to suggest that standards will remain the same, the left-leaning IPPR (Institute for Public Policy Research) concluded that the Brexit deal is ‘at risk of erosion.’

However, provisions for ‘rebalancing measures’ in the TCA could be further outlined moving forwards. These rebalancing measures would ensure that if one side ups their environmental standards, the other side would have to keep pace and do the same, or face action such as tariffs being imposed. IPPR state the rebalancing measures would ‘allow both the EU and UK to implement counter measures where divergence on standards is shown to materially impact trade or investment in a negative way’, which paves the way for future negotiations to continue on this topic.

On a similar note, there have also been concerns raised about the UK-specific regulatory bodies now required to replace those that had been run by the EU. For example, a new Office for Environmental Protection for the UK in the wake of Brexit is not yet up and running, with a chair for the organisation incoming in February and a watchdog in the chemical sector is also not fully set up yet. The Environment Bill is now also expected to be delayed until the Spring, as a result of Brexit plus coronavirus.

This has concerned some, as the existing environmental body, the Environment Agency, reported that its ‘capacity to visit and tackle polluting businesses is now significantly reduced’, despite serious incidents increasing by around a quarter between 2017 and 2018.

Electric vehicles (EVs)

Supply chains for electric vehicles (EVs) may also be facing additional costs. The SMMT had previously warned that a no-deal scenario could add £2,800 onto the cost of the average EV in the UK. Although a no-deal outcome was avoided, there are still implications in the supply chains of EVs as more administrative burdens are placed in transporting the EVs.

Initially (until 1st Jan 2024), tariff and quota free trade can occur between the UK and EU as long as the EV batteries contain at least 30% of materials made in either EU and UK factories. But from January 2027, ‘the thresholds for tariff-free electric car part trade between with two parties will tighten’, with content made in either the UK or EU needing to rise to half to be tariff and quota free.

This may represent good news for domestic EV manufacturing, but as the industry currently relies on imports from Japan and China, the longer-term threshold tightening in 2024 and then in 2027 could cause disruption.

New factories and jobs are likely to be a significant part of growth in UK EV supply chains, with estimates of around 40,000 new jobs in 2030 and £3bn of private investment from the switch to EVs. In addition, investment into EV charging infrastructure – with £1.3bn committed to accelerating the roll out – creating jobs around the country.

Nissan has already stated that it will source more batteries from Britain after Brexit to avoid tariffs, for use in its Sunderland factory – which creates 30,000 of its EV model the Nissan Leaf each year.