The health impacts of net zero

Climate change is affecting people’s health around the world in profound ways, but do you know what its impacts are in the UK?

By Tricia Curmi

Share

Last updated:

In this briefing, we’ll explore the biggest climate-driven health risks for Britain. You may already have a sense that extreme heat and flooding are increasing, and that they’re bad for us, but did you know that tropical mosquito-borne diseases like dengue pose a genuine and significant risk? Have you considered how climate change might affect what ends up on your plate, how much it costs, and the knock-on effects that has on health?

We'll also explore how tackling climate change, i.e. net zero, can improve health through measures that make our air cleaner (like EVs and heat pumps), improve our diets and make space for nature, all of which benefit the NHS by saving lives and keeping costs down.

The climate crisis is a health crisis

A 2023 study found that people in England are concerned about climate change but struggle to identify its health impacts. Where health impacts are identified, they are linked to extreme weather overseas. Few people seem to understand how climate change impacts health in Britain.

While it’s not clear to the public, health professionals are sounding the alarm. The NHS has said that ‘the climate emergency is a health emergency. Climate change threatens the foundations of good health, with direct and immediate consequences for our patients, the public and the NHS’, and that they ‘will need to address the deterioration in public health resulting from the impacts of climate change, and the demand for healthcare that will increase as a result’.

The UK Health Alliance on Climate Change (UKHACC), an alliance of UK-based health organisations representing around one million healthcare professionals, has said that ‘climate change is the greatest health threat facing humanity’.

And The Lancet, one of the world’s leading medical journals, has said that climate change is ‘the greatest global health threat facing the world in the 21st century’.

How is climate change affecting health in the UK?

The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), the part of the government that provides scientific leadership on health risks, said in their 2023 report that extreme heat, flooding, vector-borne diseases and the availability of food imports (specifically fruits and vegetables) are the most immediate climate-related health threats to the UK.

Extreme heat

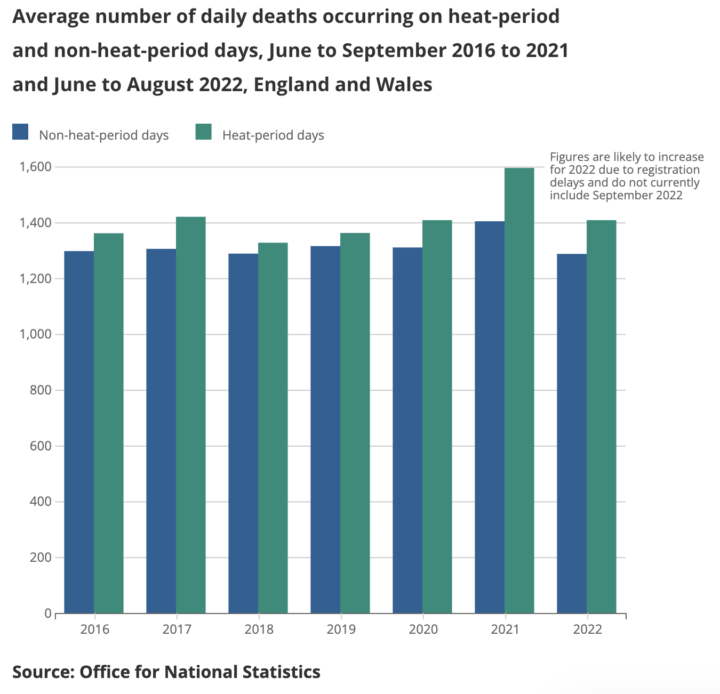

Extreme heat has already killed people in Britain and will continue to do so as temperatures rise. 2022 was the UK’s hottest year and one of the hottest years globally. There were almost 3,000 heat-related excess deaths in England that summer (June-August), when temperatures exceeded 40°C for the first time, with 387 deaths in London alone. One fifth of UK doctors reported cancellations of surgeries because the extreme heat caused staff absences, bed shortages and overheating of surgical theatres. It also resulted in the failure of IT systems at London’s largest NHS hospital trust, which impacted healthcare at three hospitals. Scientists have said that human-induced climate change made 2022’s extreme temperatures at least 10x more likely.

There were over 2,000 excess deaths in summer 2023, the third highest heat-related mortality since the government started publishing data in 2016. 2023 was the hottest year ever recorded in human history...until 2024 smashed its record. Already, experts at the Met Office are predicting that 2025 will be one of the top three hottest years alongside them.

This extreme heat is driving an increase in the number of hot nights, affecting people’s sleep. Poor sleep has negative consequences for physical and mental health and is responsible for around 8% of deaths. Southern English coastal towns are the worst affected, with Nigel Farage’s constituency of Clacton-on-Sea suffering most. Without climate change, it would have had just 1.1 hot nights per year, but because of climate change it has had 13.2 per year from 2014-2023.

Extreme heat also affects people’s ability to work. In 2023, the UK lost 8.5m potential working hours due to heat exposure, an increase of 166% on the 1990-1999 average. Construction workers were the hardest hit, accounting for 71% of potential working hours lost and 75% of potential income lost.

Treating the health impacts of extreme heat is expensive. Research has shown that, from 2001-2012, the NHS spent an average of at least £20m per year on treating excess emergency hospital admissions associated with extreme temperatures. The total cost of heat-related mortality from climate change and its associated socio-economic changes have been estimated at nearly £7bn per year in the 2020s, rising to nearly £15bn per year in the 2050s, for England alone under a medium warming scenario.

Floods

The Environment Agency’s National Flood Risk Assessment (NaFRA) found that over six million properties in England are currently at risk of flooding from surface waters, rivers, the sea or a combination. However, because of climate change, they predict this will rise to eight million, or 1 in 4 properties, by 2050.

This will expose millions of Brits to the health impacts of flooding, disproportionately affecting low-income households as they are eight times more likely to live on tidal floodplains.

Additionally, nearly two thirds (61%) of low-income renters do not have home contents insurance, making them more susceptible to the financial shock – and therefore mental health impacts – of flooding.

Mental health

Research by the government found that damage and displacement caused by extreme weather can increase the chance of mental health problems like depression by 50%. A quarter of people who have been flooded still live with these problems at least two years later.

A 2024 study on UK communities found that the risk of dying increased by nearly 7% for every unit increase in flood index. The risk of death by suicide was strongest in the flood year, while that from neurological or mental illnesses was strongest three or four years after the flood.

Farmers are particularly exposed to the mental health impacts of climate change because their income is dependent on stable growing conditions. Extreme and volatile weather in 2023 and 2024 has taken its toll on British farmers, something UKHSA is currently investigating.

Farmers are also worried about emergent livestock diseases like bluetongue, a viral infection spread by midges. Research suggests that climate change will cause bluetongue to extend further north, have a longer transmission season and larger outbreaks. Outbreaks we’d expect to see once every 20 years in the current climate could become typical every year by 2070 in England and Wales. The government recognised this risk in their Food Security Report 2021.

Vector-borne disease

The UK is at risk of at least four new vector-borne diseases – dengue, chikungunya, Zika and West Nile Virus (WNV) – as higher temperatures will enable invasive mosquitos to survive here.

UKHSA has said that the establishment of mosquito Aedes albopictus ‘is one of the most significant risks for public health posed by climate change’ in the UK. Ae. albopictus transmits dengue, chikungunya and Zika, none of which have been seen in Britain before. The area around London is already suitable for their survival, while most of England will be suitable by the 2050s. Most of Wales, Northern Ireland and the Scottish Lowlands will be suitable by the 2070s. This means that the UK could be suitable for dengue and chikungunya transmission around mid-century.

Culex modestus, the mosquito that carries WNV, is now established in coastal areas of southeast England. Temperatures are currently too low for WNV outbreaks, but the risk will increase as temperatures rise. Modelling predicts that epidemics may occur in the second half of the century, with southeast England most at risk.

This will be a surprise to most readers, who quite understandably think of mosquito-borne diseases as something that happens in far off, equatorial countries.

Climate change could also exacerbate existing vector-borne diseases in the UK. Under a worst-case warming scenario, UKHSA predicts an increase in the distribution of several UK tick species, notably Ixodes ricinus which can transmit Lyme disease and tick-borne encephalitis (TBE). A 2024 study found that, by 2080, the Scottish tick population could increase by a quarter (+26%) with 1°C of warming or double (+99%) with 4°C of warming. We are currently on track for around 3°C of warming.

Food security

The government’s Food Security Report 2021 said climate change was the biggest medium to long-term threat to the UK’s food security. The recent 2024 update mentions it 113 times, saying it presents a significant, pressing risk that ‘threatens the ability of global food production to meet demand in the longer term’.

This is because extreme weather is impacting farming both at home and overseas. The UK has just had its third worst harvest, and England its second worst, since the early 80s due to extreme wet weather, which scientists say was made 10 times more likely and 20% heavier by climate change. This caused the failure of key UK crops like cooking oils (oilseed rape), sugar beet, cauliflowers, broccoli, wheat and potatoes, at a time when climate change is also hitting the imports of these foods we get from other countries to plug the gap between domestic supply and demand.

We import around half our food, because much of it is commodities we can’t grow at commercial scale in the UK. Among the imports threatened are fresh fruit and veg from the Mediterranean, as well as staples like rice, bananas and British favourites like tea, coffee and chocolate from tropical countries, which have all been battered by climate impacts in recent years.

But it’s not just the crops that are threatened; it’s also the people that produce them. According to the Lancet Countdown’s 2024 report, an estimated 1.6bn people – over a quarter (25.9%) of the global working age population – worked outdoors in 2023. The proportion of outdoor workers was highest in least developed countries (30.8% of the workforce). Heat exposure led to a record high of 512bn potential work hours lost among these people, 49% above the 1990-99 average. 63% of these losses occurred in the agricultural sector. Again, this proportion was even higher in least developed countries, at 80.5%. If farmers can’t work, this threatens food security both in-country and overseas, as many of these goods are traded on international markets.

The average UK adult (16-64 years old) consumes 23% more saturated fat, 14% less fruit and 67% less vegetables than is recommended by the government. Diet-related ill health has a higher impact on the NHS budget than smoking, alcohol consumption and physical inactivity. For example, it is estimated that the NHS spends nearly £7bn per year on treating obesity alone, with the total cost to the economy estimated at £58bn per year (equivalent to 3% of UK GDP in 2020). Type 2 diabetes – much of which is preventable – currently costs the NHS almost 10% of its budget.

These poor diets, and the poor health that results, are killing people. In 2021, almost 39,000 UK deaths were attributed to excess consumption of red meat and dairy, while nearly 36,000 deaths were due to insufficient consumption of nutritious plant-based foods. Together, these accounted for a third (32%) of all diet-related deaths that year.

At a time when we really need to be eating more fruits and vegetables – which are associated with a lower risk of chronic diseases including obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and some cancers – climate change is making them harder to grow, which pushes up prices for consumers. Extreme weather added £361 to the average household food bill across 2022 and 2023.

Drought and fire

It’s also worth noting that, while UKHSA doesn’t rate them as the highest priority climate-related health threats to the UK, there are still dedicated chapters on drought and fire risk in their 2023 report.

The extreme heat of 2022 caused fires to break out across the UK, with the London Fire Brigade experiencing its busiest day since World War Two.

In February 2025, the National Fire Chiefs Council (NFCC) warned that the UK is not fully prepared for the impacts of climate change.

The health impacts of net zero

Lifestyle and environmental factors have been found to be 10 times more important than genes in the risk of early death. Unless we do something about it, climate change will make it much harder for us to achieve healthy living conditions.

Climate change is being caused by humans burning fossil fuels. This releases huge amounts of ‘greenhouse gases’ (GHGs) into the atmosphere; the planet is warming up because these gases trap heat.

Net zero is the solution to climate change because it drastically reduces these emissions. It means that GHGs going into the atmosphere must be balanced with those being removed, to ensure the net change each year is zero. The UK has a legally binding target to reach net zero by 2050, which is why we need supportive government policy to help us get there.

Public support for net zero is strong, with two thirds of Brits in favour. This is true even among Reform voters, with 42% of them saying they support measures by the government to reduce GHG emissions to reduce the risks of climate change. Reform have pledged to scrap net zero, but only 4% of their voters vote for them because of this policy.

However, it's possible that public support for net zero could be even higher if people fully understood its health benefits, given that health is consistently one of the top three voter issues.

Firstly, it will slow global heating and the extreme weather it’s driving, protecting people from the threats outlined here and in this briefing. Secondly, many net zero policies have health co-benefits.

Cleaner air (and more exercise)

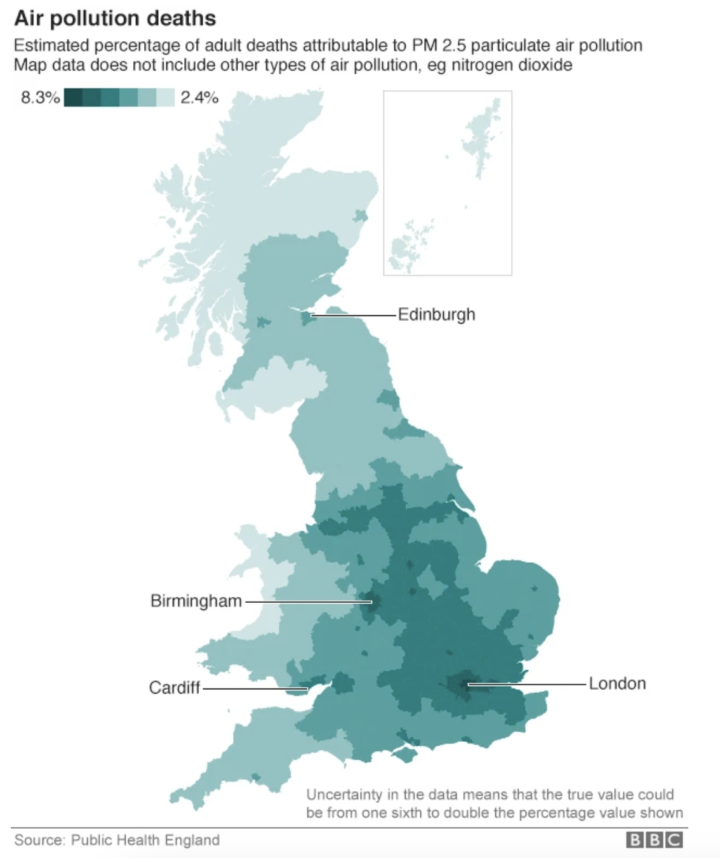

In 2021, almost 30,000 deaths were attributed to PM2.5 (‘fine particulate’) air pollution in the UK, with fossil fuels contributing to almost half of them (44%, or around 13,000 deaths).

Research by the Clean Air Fund, which modelled the potential impacts of existing policies and the ongoing electrification of the UK’s vehicle fleet, found that air quality benefits could translate into a 23% reduction in average exposure to PM2.5, 3,100 fewer new cases of coronary heart disease per year, over two months longer life expectancy per person and economic benefits of up to £384bn.

A 2025 study looked at the net zero pathways for transport and buildings in the UK’s sixth carbon budget, finding that less air pollution and an increase in active travel (walking, cycling and e-biking) generated health benefits. These included 1,500 fewer COPD cases, over 1,400 fewer childhood asthma cases and over 800 fewer strokes on average every year.

These projections are consistent with real-life health improvements seen in Bradford’s clean air zone. Research has shown it saved the NHS nearly £31,000 per month in its first year, with GP visits for both respiratory and cardiovascular illness down by a quarter (25% and 24%, respectively).

Gas boilers are a significant source of nitrous oxides (NOx), gases that cause inflammation of the airways and increased susceptibility to respiratory infections. Prolonged exposure is associated with decreased life expectancy. Analysis has shown that the UK’s gas boilers produce 863% more NOx per year than all its gas power stations combined. Switching to electric heat pumps removes these pollutants.

The NHS has said that meeting the UK’s climate ambitions under the Paris Agreement could save almost 44,000 lives every year: 5,700 from improved air quality and 38,000 from a more physically active population.

Better diets

UKHSA has said that eating less meat and more plants will reduce GHG emissions, energy use, the risk of zoonotic diseases (those that jump from animals into humans) and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) whilst improving biodiversity and population health.

Recommendations for a climate friendly diet overlap with recommendations for a healthy one. WWF’s Livewell guide for sustainable eating closely aligns with the government’s Eatwell Guide for health. People who demonstrate intermediate to high adherence to the Eatwell Guide have 30% lower dietary GHG footprints and a 7% reduction in total mortality risk compared to those with very low adherence.

The NHS has said that meeting the UK’s climate ambitions under the Paris Agreement could save over 100,000 lives every yearfrom healthier diets rich in plant-based foods.

But it’s not just lives saved; it’s money too. The Conservative Animal Welfare Foundation found that, if Brits only ate meat-free lunches on weekdays, improved health could save the NHS over £2bn per year. Making meat-free the default option in public catering could save an additional £74m per year.

More nature

To get to net zero, we also need to restore hectares of woodland and peatland, which naturally absorb emissions from the atmosphere. These environments have multiple health co-benefits.

Firstly, they provide places to exercise. The lifetime physical health benefits of woodland (due to increased activity levels) are estimated to be between £5,000-£12,500 per hectare, depending on the type of woodland.

Secondly, they protect communities from flooding by catching and storing rain, stabilising soil and creating barriers to stem the flow of water, thereby limiting its physical and mental health impacts. In 2022, the total cost of mental ill health in England was £300bn, equivalent to double the NHS’ entire budget that year. Given that 1 in 4 English properties will be at risk of flooding by 2050, and these events can increase the likelihood of developing mental health problems by 50%, natural environments could help to keep costs down for the NHS.

Learning from the recent past

The climate emergency is the next global health emergency waiting in the wings. It would be wise to learn from the Covid pandemic and prepare, doing everything we can now to lessen its impact: that is net zero.

Those pushing to scrap this policy are disregarding its fundamental role in improving health, saving lives and protecting the already overburdened NHS by reducing care demands and saving money.