COP29: what was achieved and what next

After two tough weeks of negotiations, and a turbulent geopolitical backdrop, we take a look at what was achieved, and what lies ahead for Brazil and COP30.

By Gareth Redmond-King

@gredmond76Share

Last updated:

COP29 came to an end in the early hours of Sunday morning in Baku. It has set a new climate finance goal, finally concluded rules on carbon trading, and edged work along on raising ambition to cut emissions. The COP presidency was chaotic, and developing countries leave the COP angry at the process, and at a finance agreement insufficient to enable them to adapt to and pay for the costs of worsening climate impacts. Despite talk that Trump would overshadow the talks, though, efforts in Baku by almost all nations demonstrate a world committed to continuing the work to tackle the climate crisis. All eyes now turn to new targets from all nations over the coming year, and what the Brazilian President has dubbed the turnaround COP, due to be hosted in Belem next year.

The top line goal of COP29

Parties came to Baku with an urgent job to do; one they had singularly failed to make any progress on in meetings throughout the year. They needed to agree how much more finance they will provide for developing countries from 2025. In 2009, they agreed to $100 billion a year by 2020; a goal that was delivered, two years late. And the finance provision from rich to poor nations was built into the Paris Agreement.

As climate change impacts worsen, though, according to expert analysis $100 billion doesn’t come close to meeting the need. Not enough of it is targeted to support adaptation to those worsening impacts, and too much is in the form of loans, adding to developing nati0ns’ debt burden. Increasingly, the poorest people in the poorest nations are bearing the burden of having to pay more for the costs of loss and damage caused by climate-driven extreme weather events. They cannot afford to adapt, and their leaders’ options become harder as demands on their countries’ limited finances grow, leaving them choosing between recovering from disaster, and paying for basic public services.

What was agreed

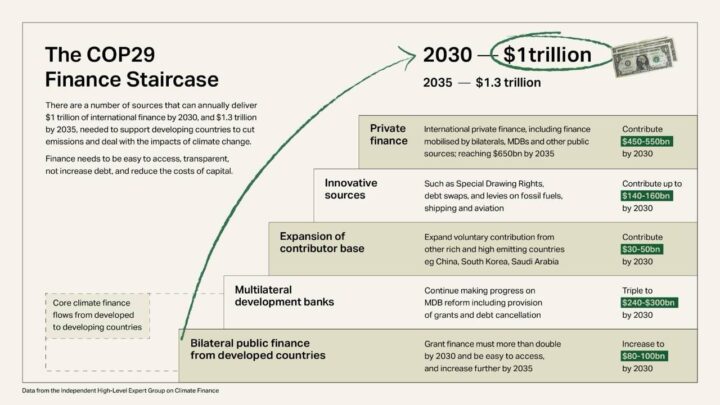

The adopted text refers to everyone working together to scale up to at least $1.3 trillion a year by 2035. However, the actual goal which it adopted for developed countries to produce is ‘at least’ $300bn a year. Whilst trebling the previous goal, this is lower than developing nations were pushing for and need; some argue it’s barely an inflationary rise. This will very much be seen, therefore, as a floor, rather than a ceiling and there will be intense pressure on developed countries to ensure that it is all public money – from governments, multi-lateral development banks, and new global taxes such as that on the ultra-rich, which the G20 discussed. There is a work programme to draw up a roadmap to the $1.3 trillion, a review point in 2030, and reference to the contributor base widening on a voluntary basis. Whilst this last was fairly hard fought, it is worth noting that China referred to its existing ‘South-South’ financing of developing nations as climate finance for the first time, and the World Resources Institute calculated it already to be worth $4.5 billion a year.

This is not charity

“Let’s dispense with the idea that climate finance is charity”, UN climate chief Simon Stiell told delegates a few days ago:

“Do you want your grocery and energy bills to go up even more? Do you want your country to become economically uncompetitive? Do you really want even further global instability, costing precious life? … An ambitious new climate finance goal is entirely in the self-interest of every single nation, including the largest and wealthiest.”

Food security

We see that here in the UK, newspaper frontpages scream that we’re “sending money to foreign farmers” as if it is a scandal. Yet we import two fifths of all our food from overseas. Much of it either can’t be grown here, or we can’t grow enough of it year-round. So of course we rely on farmers overseas for crops like rice and banana. And as droughts, extreme heat, floods, and climate change-fuelled pests and disease threaten more and more of those farmers, and their crops if we do not help them to adapt, harvests are hit, there are shortages, and prices rise.

Over the last two years alone, climate impacts have added £360 to the average household food bill in the UK. British people get this – more than half are worried about food security, and nearly two thirds support provision of climate finance to people who need it overseas – we pay up to the equivalent of 0.2% of annual public spending in overall climate finance each year. They particularly support it when it is effective, aids self-sufficiency, and there is a benefit for the UK. The UK supports projects in many countries that supply us with food, and as some foods are hit by climate impacts abroad, and at home (the UK had its wettest winter in 2024), if we don’t support farmers in the UK and overseas, our food security will increasingly be hit.

Global ambition

The fact that so much attention has been on the NCQG – the new collective quantified goal on climate finance – has, to some extent, meant less progress elsewhere. The other area of focus for this COP was implementing the Global Stocktake (GST), which was landed at COP28 in Dubai. This included the landmark commitment to transition away from fossil fuels, and committed parties to trebling renewables, doubling energy efficiency and halting and reversing deforestation – among other things.

This is important for the coming year, when all parties are required to produce updated NDCs – nationally determined contributions. These are each country’s commitments on how they will implement the Paris Agreement, with the headline item being their pledge to cut emissions. The UK introduced their new NDC – an 81% emissions cut by 2035 – in Baku, along with last year’s COP hosts the UAE, and next year’s, Brazil. This was hailed as welcome leadership, with the UK’s in particular setting the bar for others to meet.

The GST sets the direction for that, so the more explicit it is about what an NDC should do to raise ambition and cut emissions, the better. Not least as we are, on current pledges, on track for something between 2.6°C and 3.1°C of temperature rises this century. Catastrophic levels, compared to the 1.5°C target in Paris, and the already devastating impacts we see at around 1.3°C of warming already.

Where we got to

In the end, whilst some progress was made in negotiations on areas like the mitigation work programme, the just transition work programme, and UAE dialogue which contains the detail of what was agreed in Dubai, there is little that comes out of COP29 on this. This is in no small part down to the efforts of blockers like Saudi Arabia, but it also owes something to the trading that has been going on around the finance negotiations.

However, even with some work programmes remitted to mid-year meetings between COPs, and whilst a reaffirmation of the scale of work needed next year would have been preferable to many, nothing is actually lost. They were agreed in Dubai, at COP28, as part of the Global Stocktake outcome. They are locked in and are not lost for want of being set out again here. And crucially, momentum on the clean transition continues apace as a result.

Signals and outcomes

On other solid outcomes, Article 6 carbon trading rules were finally concluded, and the gender programme – which had been threatened by blockers during negotiations – has been extended for another 10 years.

But there were important signals over the last two weeks also, from Baku and the G20 in Rio. Leaders reaffirmed commitment to 1.5°C and speeding up the clean energy transition. There was strong leadership at COP with the new NDCs from the UK and others, the forming of the UK-led Clean Power Alliance to speed the switch away from fossil fuels, and a call from a group of high ambition countries for NDCs to include commitments to no new coal. Indonesia announced they would retire all their coal fired power stations over the next 15 years, and China made helpful interventions that signalled their willingness to help move the climate finance discussions forwards.

Trump, despite speculation before the summit, did not loom over it. Rather, global momentum on clean transition leaves most confident that, having failed once to halt that and stymie the international talks process, he will now fail a second time. He will also fail to halt progress in the US itself. Climate Action Tracker calculates his actions may only add just 0.04°C to global temperature rises; not ideal at a time when we’re behind schedule to net zero emissions, but also not the disaster many headlines foretold. And civil society is mobilising already in the US, as it did last time – America’s All In was at COP and it is clear that states, companies, organisations and citizens will, as last time, work to ensure that climate action continues in the US.

What next

After any COP, there are always those who say it doesn’t work and we should ditch it. But this process is working, albeit frustrating slowly for many. It is the UNFCCC COP process that brought the world to the landmark Paris Agreement, and beyond – which took us from apocalyptic levels of projected warming little more than a decade ago (5°C+) to being on track for around half that now, if all countries deliver on their pledges. And the momentum towards a clean energy future is considerable – investment in renewables running at twice the rate of that into fossil fuels, with the International Energy Agency forecasting demand for the latter will peak by the end of the decade.

This also remains the only global process where the poorest nations have a seat around the table with the rich.

On both momentum and inclusion, not only does the process still work, but it is also all we have. All parties feel the need to be there, engage, and set targets within the process – even those like Russia who are committed to fossil fuels, or those like Saudi Arabia who work to block and delay. Russia’s chief negotiator even, during COP29, called on Trump to keep the US in the Paris Agreement once he takes office. If we ditch this process, we will have nothing in its place, and no hope of designing and implementing anyone’s imagined better alternative.

Hopes are high for progress in Belem.

Share